The College Enrollment Plunge Is a Correction, Not a Crisis

Americans are becoming smarter shoppers when it comes to higher education—and it’s producing better results.

September 25, 2025If there was an era we might call “peak higher education,” it was right after the Great Recession. Unemployment spiked, especially among younger people. Those who couldn’t find work, or who wanted to advance their careers at a time when promotions were scarce, turned to higher education for a leg up. Millions took the opportunity to attend college or go back to complete their degrees rather than take their chances in a weak labor market.

As the economy cratered, Congress obliged the swelling demand for higher education with more funding. Higher student loan limits, heftier Pell Grants, and the new American Opportunity Tax Credit all fueled the college craze. Leaders offered moral encouragement as well. In 2009, President Barack Obama set a goal of making the United States the most-educated nation in the world. And who can forget Michelle Obama’s infamous “you should go to college” rap video?

As the economy cratered, Congress obliged the swelling demand for higher education with more funding.

College enrollment duly spiked. The number of undergraduates on college campuses peaked at 18 million in fall 2010. Open-admissions colleges that specialize in enrolling marginal students ramped up. The University of Phoenix—the nation’s most famous online mega-college—enrolled a third of a million students in the fall of 2010.

The federal government’s proximate goal of increasing college enrollment was a smashing success. But in retrospect, the era of peak higher ed looks like a mixed bag. Advocates celebrated more students going to college and bettering themselves. But many students left school with a bitter taste in their mouths.

Many of the marginal students never finished college at all. In 2008, the six-year completion rate at the University of Phoenix was a mere 9 percent. Barely one-fifth of students who attended community college finished their programs, and many of those who did couldn’t transfer their credits to a four-year school. New college graduates found themselves employed in lower-wage jobs that had not traditionally required bachelor’s degrees. Millions felt they had poured time and money into college yet had little to show for it.

Barely one-fifth of students who attended community college finished their programs, and many of those who did couldn’t transfer their credits to a four-year school.

Student loans compounded the resentment. Colleges gleefully encouraged their students to take on debt, promising that the benefits of a college education would allow borrowers to repay with ease. It worked out for some people. But millions of others, especially those who took on debt but didn’t finish school, found themselves with unaffordable loan payments. Loan repayment rates plummeted. The saga culminated in President Joe Biden’s ill-starred (and wildly expensive) attempt at mass debt cancellation.

Pride goeth before the fall, and the stage was set for a collapse in college enrollment. An improving economy and flat growth of new high school graduates contributed, but so did a drop in public confidence in higher education.

Enrollment fell steadily from 2010 onward. By fall 2023, there were 3.2 million fewer undergraduates seeking degrees on college campuses than there were in the throes of the Great Recession. Many defenders of higher education have called this a crisis.

But new research I recently published at AEI shows that the college enrollment plunge is the opposite of a crisis. In fact, it’s an overdue correction.

The colleges doing a good job—those offering high-quality degrees at reasonable prices and graduating most of their students—aren’t the ones losing enrollment. Rather, almost all of the drop in student numbers is from low-quality colleges—those schools that students would likely be better off avoiding in the first place.

Measuring College Quality

To get to the bottom of what’s really driving changes to student enrollment, I set out to measure the change in student numbers at high- and low-quality institutions.

To define quality, I used four different measures of student outcomes: the share of students who finish their degrees within 150 percent of the normal time to completion, the rate at which borrowers pay down principal on their student loans, the rate at which borrowers default on their loans, and the median earnings of former students after leaving school. While these variables all measure different things, they tend to be correlated with one another: a school with a low graduation rate usually has a low loan repayment rate. I therefore create a composite measure of each college’s outcomes in 2010, weighting the four variables equally.

Using this measure to divide colleges into five equal-sized groups, or quintiles, based on their enrollment in 2010 immediately reveals huge disparities in educational quality. Students who attended a college in the bottom quintile graduated at a rate of 16 percent, compared to 72 percent for the top quintile. Students attending schools in the bottom quintile are seven times more likely to default on their loans. They also earn just $30,000 per year, compared to $50,000 for the top quintile.

Students who attended a college in the bottom quintile graduated at a rate of 16 percent, compared to 72 percent for the top quintile.

Students who attend higher-quality colleges obviously end up much better off. Some of this is likely due to the characteristics of the students they enroll. Open-enrollment colleges in the bottom quintile probably enroll students with worse grades in high school, who struggle to pass their college courses and graduate on time.

But much of the disparity in outcomes is likely due to institutional quality. Some colleges do better by their students than others. Moreover, the fact remains that the outcomes a typical student can expect if they attend a low-quality college are much worse. If attending a higher-quality school isn’t an option, many of those students would be better off not attending college at all.

Trends in College Enrollment, 2010–23

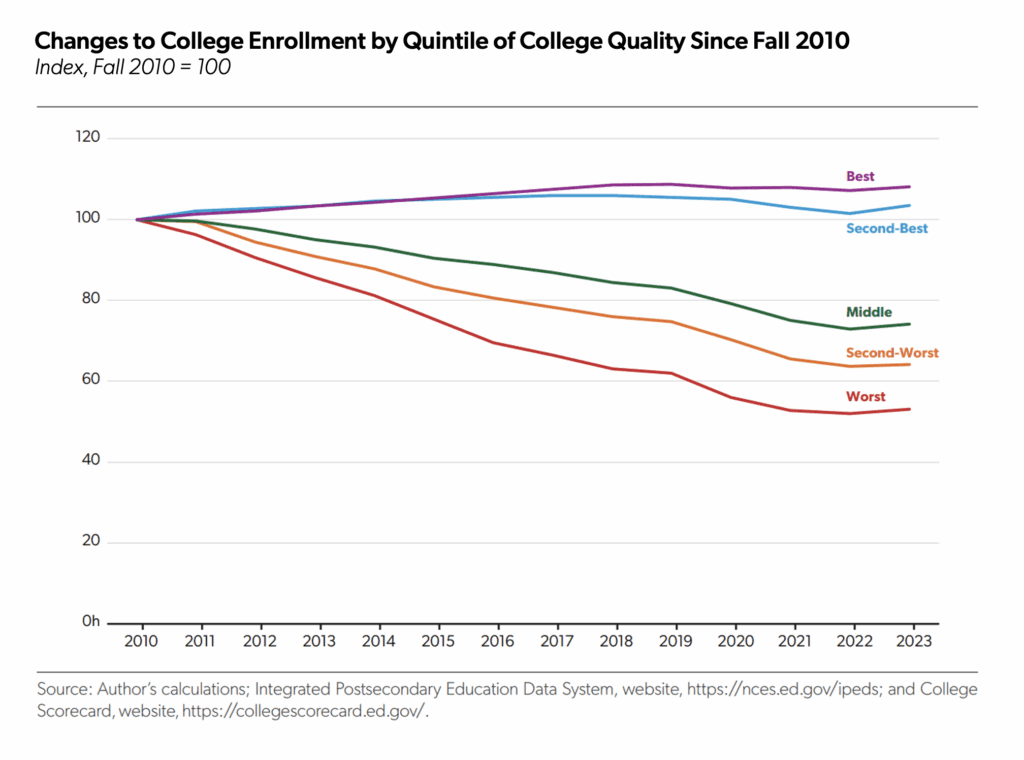

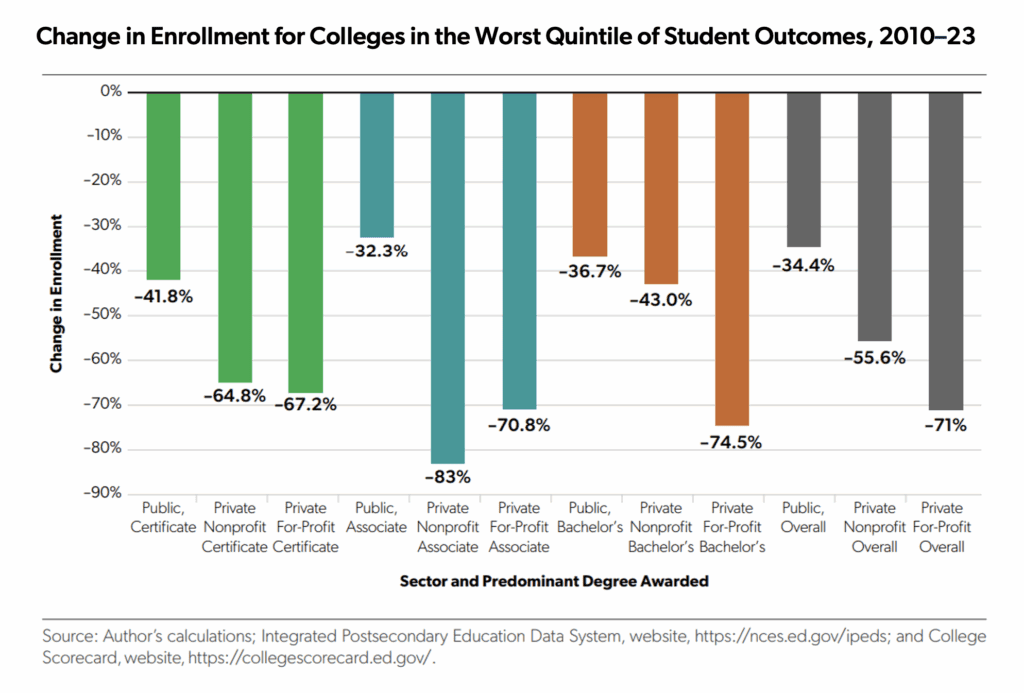

Dividing colleges into groups based on their outcomes reveals stark changes in their aggregate student numbers over time. The lowest-quality colleges saw the biggest plunge in enrollment: Schools in the bottom quintile lost 47 percent of their undergraduates from 2010 to 2023. The University of Phoenix—the largest college in the bottom quintile in 2010, with over 330,000 students—lost three-quarters of its enrollment. The mega-school has shrunk so much that the University of Idaho has seriously explored an acquisition.

But high-quality colleges did well. Schools in the top quintile increased their enrollments by 8 percent between 2010 and 2023. Some institutions, especially large public universities, grew by double digits or more. Texas A&M University swelled from 40,000 undergraduates to nearly 60,000. Far from suffering an enrollment collapse, schools with good outcomes are doing better than ever.

Overall, half the decline in college enrollment since 2010 is attributable to schools in the bottom quintile. Nine-tenths of the decline is explained by the schools in the bottom two quintiles. This is not a crisis, but a correction.

In the bottom quintile, the biggest drops in enrollment occurred at large for-profit colleges like the University of Phoenix, ITT Technical Institute, and Kaplan University (now a part of Purdue University). But community colleges with poor outcomes also bore their share of the decline. Major community college systems like Houston Community College and Pima Community College witnessed double-digit plunges in enrollment. In the bottom quintile, every sector of higher education bled massive numbers of students—from trade schools and community colleges to full-fledged universities.

The College Major Revolution

These changes in patterns of student choice do not stop with choice of institution. As students shun colleges with worse outcomes, they are also increasingly choosing fields of study with a stronger return on investment.

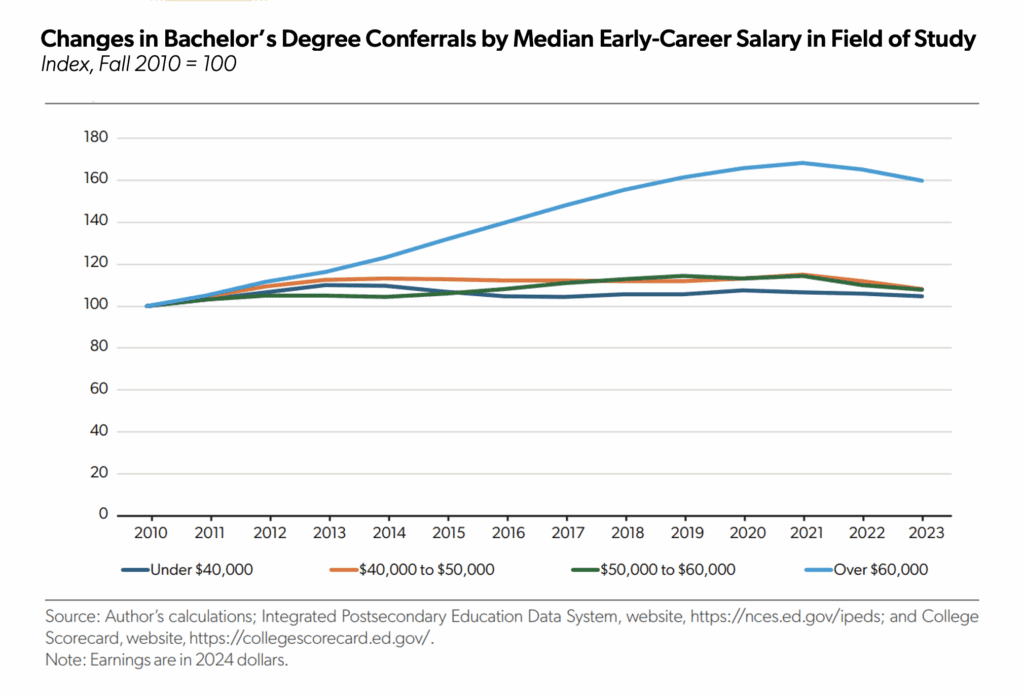

While college enrollment has fallen, the number of students earning bachelor’s degrees has actually risen—largely because the enrollment decline is occurring at schools with low graduation rates, where most students don’t earn degrees anyway. But the types of degrees that graduates earn are shifting. Almost all the rise in bachelor’s degree attainment has occurred among majors with high starting salaries.

As students shun colleges with worse outcomes, they are also increasingly choosing fields of study with a stronger return on investment.

The number of bachelor’s degrees conferred in fields where the median starting salary is above $60,000, such as mechanical engineering, nursing, and accounting, increased 60 percent since 2010, with even larger increases for some majors. Computer science degrees, for example, have tripled in popularity since 2010.

Bachelor’s degree conferrals are stagnant elsewhere. Between 2010 and 2023, the number of degrees awarded in majors with starting salaries below $60,000 has risen by less than 10 percent. Many of the lowest-earning majors have seen decreases. English literature degrees are down 39 percent. Sociology is down 18 percent. Philosophy has fallen 19 percent.

Similar trends have occurred among other undergraduate credentials, including associate degrees and certificates. The number of credentials awarded in precision metalworking (including welding) rose by 91 percent from 2010 to 2023. Marco Rubio famously lamented in a 2015 presidential debate that America needs “more welders and fewer philosophers.” He seems to have gotten his wish.

Learning with Their Feet

If you care about tangible results, many trend lines in higher education are pointed in the right direction. Low-quality colleges are losing students in droves. Students are choosing majors with more economic upside. Higher education may be smaller—but it’s producing better results.

Students’ desire for economic returns from higher education is well established. According to a Gates Foundation survey, high school students’ top stated reason for obtaining a college degree is “to be able to make more money.” While other reasons for pursuing higher education are important to students as well, financial considerations are paramount.

Prospective college students probably don’t spend hours poring through spreadsheets of outcomes data trying to optimize their college pathway. But information about institutional quality spreads in other ways, like word of mouth and social media. Perhaps your neighbor or cousin attended a certain school, found the courses lacking, didn’t finish their degree, and ended up with student loan payments they couldn’t afford. They told you about their experience or posted about it online. You decided not to make the same mistake.

Prospective college students probably don’t spend hours poring through spreadsheets of outcomes data trying to optimize their college pathway. But information about institutional quality spreads in other ways, like word of mouth and social media.

These trends are also linked to a general loss of confidence in higher education: The share of Americans who believe college is worth the cost has plummeted. Marginal students—those already on the fence about whether to attend college—were probably most likely to change their minds when the national mood shifted. These types of students disproportionately filled seats at lower-quality, open-enrollment schools.

Some may be concerned that these marginal students are avoiding college entirely rather than moving to higher-quality schools. While colleges with good outcomes have expanded, it hasn’t been nearly enough to absorb the enrollment drop at lower-quality institutions. While there is no guarantee that marginal students would do as well as their peers already attending high-quality colleges, there are rigorous causal studies showing that choice of institution can improve a student’s outcomes.

Expanding high-quality schools to serve more qualified students is a laudable policy goal. But for marginal students, skipping college entirely may be a better option than enrolling in a school with poor outcomes. If I were a potential student and my chance of graduation were 16 percent and expected earnings no better than a typical high school graduate, I probably wouldn’t take those odds. Many students seem to have grasped this reality and dispensed with the college-or-bust mindset that gripped prior generations.

The market for higher education is imperfect, distorted as it is by government subsidies. But it remains a market where consumer choice plays a key disciplining role. Political scientists say taxpayers “vote with their feet” by moving to jurisdictions with better policies—witness the exodus of Californians to Texas. Students are doing something similar by fleeing low-quality colleges. Call it “learning with their feet.”

Preston Cooper is a senior fellow in higher education policy at AEI. Follow him on X at @PrestonCooper93.