The US Postal Service Is Going Broke

America’s Postal Service turned 250 years old this year. Does it have a future?

September 25, 2025The US Postal Service (USPS) recently reported its third quarter financials, tallying a loss of $3.1 billion. That is 21 percent higher than the agency’s shortfall during the same period last year and the latest sign of the Post Office’s increasingly dire state.

At its core, the Post Office is sinking. The $18.8 billion it earned in revenue during the third quarter was no higher than its earnings in the previous year. Meanwhile, its expenses were $22 billion or 2.9 percent higher than the same period last year due to rising employee compensation costs. The Post Office has $15 billion in debt, its legal maximum, and has lost $6.2 billion this year—so far.

If this news was not bad enough, the USPS’s revenue has taken a hit in recent weeks due to a plunge in international mail. Around 90 countries suspended parcel deliveries to the United States after President Donald J. Trump suspended the de minimis exemption for goods worth less than $800. Now stiff tariffs must be paid, and incoming volume has dropped perhaps 80 percent.

At its core, the Post Office is sinking.

The irony is that all this bad news came just weeks after the Post Office celebrated its 250th anniversary. The agency has a storied history. It was created in 1775, one year before the American colonies declared independence from Great Britain and nearly 15 years before the adoption of the US Constitution. Benjamin Franklin was its first leader, and other famed Americans from Abraham Lincoln to author William Faulkner and musician Charles Mingus have worked there. The agency has moved mail by foot, horse, mule, carriage, steamboat, trolley, motorcycle, plane, truck, car, bus, and even pneumatic tube.

Letter carriers on scooter, circa 1916. Credit: US Postal Service.

Today, the US Postal Service is a colossal organization, with 639,000 employees working in or out of 31,000 properties. The agency handles 44 percent of all the mail sent worldwide and processes 371 million pieces of mail each day, which it delivers to 169 million addresses. Last year the agency earned $79.5 billion in revenue.

Yet the Postal Service’s future is very much in doubt. The self-funding agency, which gets essentially no support from taxes, has run deficits most of the past 15 years. Two years ago, the USPS had more than $18 billion in liquid assets available for paying its operating costs. Now it has only $10 billion in cash. To preserve cash, the agency has skipped making billions of dollars in payments into its retirees’ pensions and health benefits fund. Nonetheless, the USPS will burn through that money in the next few years.

What happens then? The agency will shut down and an ungodly mess will ensue unless taxpayers bail it out.

To preserve cash, the agency has skipped making billions of dollars in payments into its retirees’ pensions and health benefits fund.

This is because the USPS remains embedded in the American economy. Publishing companies annually send 681 million copies of magazines and journals through the mail. Small businesses and community newspapers rely on the USPS to deliver advertising flyers, particularly in rural areas. A 2019 survey found pharmaceutical companies delivered 170 million prescriptions by mail each year, a number that likely has gone up as America’s population has gotten bigger and grayer.

Government agencies would also be left scrambling. In 2024, the USPS delivered 99 million ballots, including those cast by military personnel stationed overseas. State governments use the Postal Service to send residents new license plate tags and jury duty summonses. The US State Department relies on the Post Office to make passport application services accessible to most Americans.

The USPS even plays a role in homeland security. In the event of a biohazard attack, the agency is tasked with delivering medicines to those who are affected. Not to be forgotten is that the USPS delivered 380 million test kits during the first two years of the COVID pandemic.

Present-day letter carrier. Credit: Smithsonian National Postal Museum.

The Post Office’s troubles stem from a basic fact: Its business model is broken. Back in 1970, Congress transformed the struggling government bureau. Gone were the days when taxpayers had to contribute to its operating costs. The US Post Office became the US Postal Service, an “independent establishment of the executive branch.” Its business model was cribbed from other federal government corporations, such as the Tennessee Valley Authority, which granted an agency a monopoly on a profitable line of business, and gave it operational freedom and some price-setting authority.

The Post Office’s troubles stem from a basic fact: Its business model is broken.

One major aim of this new model was to curb politicians from meddling in USPS operations and making them less efficient. Hence, no longer would the agency go hat in hand to Congress for appropriations, which inevitably came with mandates. Instead, the new USPS would fund itself by selling stamps—purchasers of postage, not taxpayers, would bear the costs. The days when the president could appoint a crony to serve as postmaster general ended. The USPS Board of Governors, who were presidentially appointed and Senate confirmed, would choose the agency’s head. The law also freed the agency from much red tape, empowering it to arrange its operations as it saw fit. When the Postal Service wanted to buy new vehicles or close facilities, it did not need to get congressional approval, as most agencies do.

This self-funding model worked reasonably well for four decades. Rising volumes of mail enabled the USPS to cover the costs of delivery to the ever-growing number of homes and businesses. First-class mail, which offered Americans faster delivery and privacy from government inspectors’ snooping, was a cash cow. The tens of billions of dollars pouring into the USPS also enabled it to pay the compensation of its workforce, about 90 percent of which is represented by four unions with the right to collectively bargain over wages, benefits, and working conditions.

The death rattle began in the late 1990s as more and more Americans hopped on the internet. Email became a go-to means of communication and began eating into letter mail. First-class mail volume peaked at 103.6 billion pieces in 2001, then began an irreversible slide.

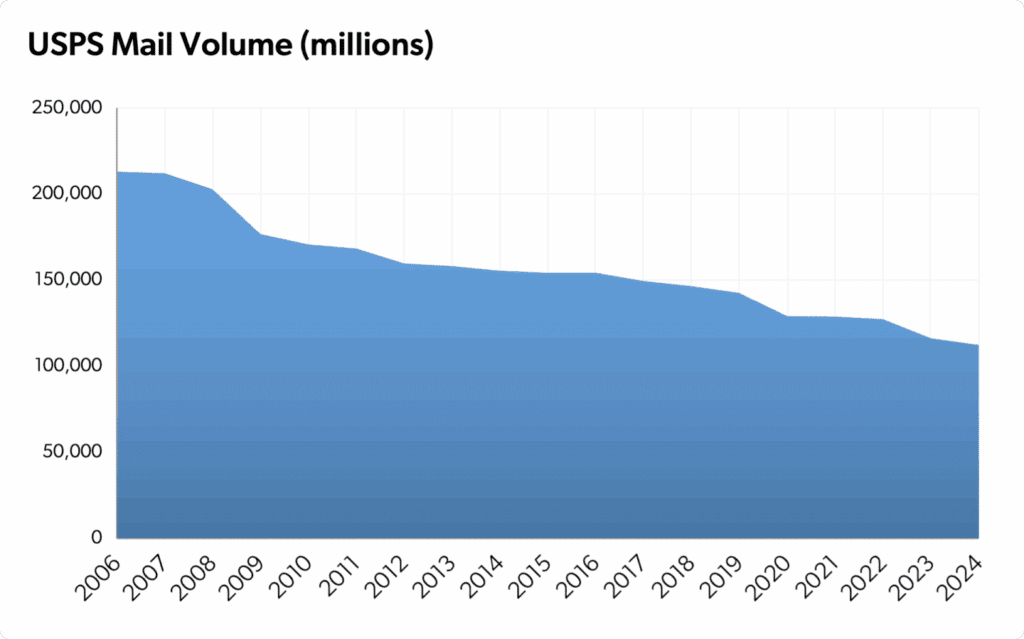

The rattle became louder in 2006. That was when the volume of all mail began to decline from its peak of 213.1 billion pieces per year. Big mailers, such as credit card companies, were moving their customer communications to digital means. The Great Recession of 2008 accelerated that process, as did the growing ubiquity of cellular phones. Last year, the Post Office handled only 112.5 billion mail pieces, a 47 percent decrease from 2006. There were only 44.3 billion first class letters, 57.2 percent fewer than in 2001.

Source: Postal Regulatory Commission.

In 2007, then Postmaster General John Potter was the rare public official who saw the writing on the wall. He told Congress the agency’s “business model remains broken. . . . With the diversion of messages and transactions to the internet from the mail, we can no longer depend on printed volume growing at a rate sufficient to produce the revenue needed to cover the costs of an ever-expanding delivery network.”

Few legislators on Capitol Hill listened or were willing to squarely face the USPS’s existential peril. They held hearings and heard mostly from the same witnesses they always consulted: postal union representatives, corporations that sent lots of mail, USPS executives, and the occasional civil servant from the Government Accountability Office or Congressional Research Service. These witness choices produced conversations that were based upon the premise that the status quo was sustainable so long as a few adjustments were made. The wonks calling for Congress to rethink the purpose of the USPS in the 21st century were mostly kept outside the Capitol’s hallowed hearing rooms.

Few legislators on Capitol Hill listened or were willing to squarely face the USPS’s existential peril.

Legislators were mostly happy to indulge in the fantasy that the USPS could survive by delivering more packages. They argued that, while the internet took away revenue from letter mail, it would give it back in the form of parcels carrying stuff ordered online.

The COVID-19 pandemic stoked this hope. In its midst arrived a new postmaster general, Louis DeJoy, a former logistics industry mogul. He tried to save the USPS by retooling it to handle more of the incredible surge of parcels ordered by Americans cooped up in their homes. By 2023, about 40 percent of the Post Office’s revenues came from postage on parcels.

Congress also offered some aid to the ailing agency. As part of a gigantic pandemic relief bill, Congress delivered what effectively was a grant of $10 billion in taxpayers’ dollars to the agency. This was the first significant congressional appropriation for the agency in many decades. Congress subsequently gifted the USPS $3 billion to help it replace its aging vehicle fleet with new electric-powered trucks and shifted $100 billion of postal retirees’ health benefit costs from the USPS to Medicare. With these aid packages, legislators were tacitly admitting the Postal Service’s run as a self-funded entity was over. Yet they have shown no signs of making it official.

Yet none of this largesse could fix the agency’s broken business model. And turning the USPS into a parcel delivery company has not worked.

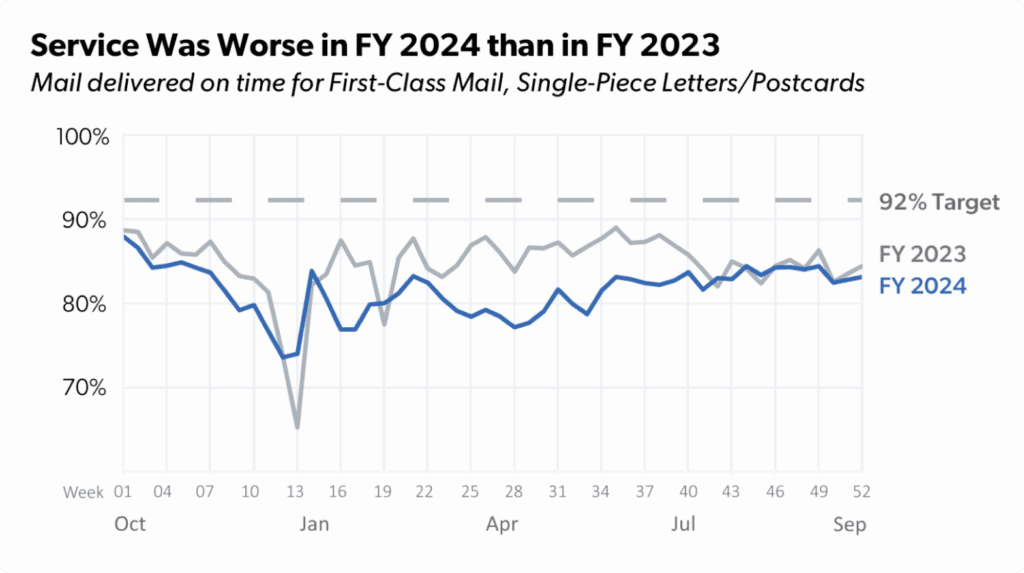

In reality, reworking the postal logistics network caused on-time delivery rates to plunge. Postal employees found themselves overwhelmed and ill-equipped to handle the flood of boxes. It is not difficult to see why. From letter carriers’ leather bags to the blue collection boxes on street corners to post offices to postal trucks and mail sorting machinery–the Postal Service was built to carry letters and other forms of paper mail. Its infrastructure was not designed to handle diversely shaped boxes carrying swords, sex toys, cereal, and just about everything all the other things consumers and businesses buy online.

In reality, reworking the postal logistics network caused on-time delivery rates to plunge. Postal employees found themselves overwhelmed and ill-equipped to handle the flood of boxes.

The whole strategy was extremely risky and amounted to wish-casting. A US government agency would switch its line of business and move from a monopolist to a firm competing with private sector giants like FedEx, Amazon, and UPS. What could go wrong?

The delusion of it all became painfully apparent after the pandemic faded. The total volume of parcels dropped, and the USPS warned in 2022 that it would run a deficit because big shippers like Amazon were giving fewer boxes to the postman.

The strategy was also expensive. The Post Office calculated it would cost $40 billion to reinvent the USPS as the government version of FedEx. And the USPS does not have $40 billion or anything close to that.

Source: Postal Regulatory Commission.

Louis DeJoy quit as postmaster general earlier this year. Dissatisfied mailers and postal union leaders have called for an end to the efforts to reinvent the USPS’s logistics network. It is unclear what David Steiner, the agency’s new leader, will do.

Nor is it clear there is anything he can do to stop the Post Office from circling the drain. The law that created the US Postal Service remains frozen in amber, establishing that “the Postal Service shall have as its basic function the obligation to provide postal services to bind the Nation together through the personal, educational, literary, and business correspondence of the people.”

Those words were written when long-distance telephone calls were fantastically expensive for most consumers, and facsimile machines were few. Pop songs of the time, like Rod Stewart’s 1972 hit, “You Wear It Well,” spoke of lovers writing precious letters to one another. When letter carriers illicitly went on strike in 1970, President Richard Nixon called up National Guardsmen and directed them to help sort the mail. He told the nation in a televised address that the wildcatters were “cutting essential service to thousands—millions of Americans.” Mail was a central means for Americans to correspond, transact business, and hear from the government.

Plainly, those days are long, long gone. When I ask anyone under the age of 30 whether they use the Post Office the answer almost inevitably is “rarely.”

To be sure, the Post Office still has plenty to do. People enjoy voting and receiving their prescription drugs by parcel, among many other modern conveniences enabled by mail. Many advertisers still see value in paper-based communications, and publishers and booksellers also depend on the postman. Local governments use USPS, too, for everything from tax bills to jury summons.

When I ask anyone under the age of 30 whether they use the Post Office the answer almost inevitably is “rarely.”

But the fact is, demand for the USPS’s services is far lower than in the past, and correcting its course requires first recognizing this reality.

Policymakers on Capitol Hill should promptly start a conversation about the Post Office that centers on two questions: What, if anything, do Americans want from the USPS in the 21st century, and how will we pay for it? Legislators should make these inquiries outside of Washington, DC, where they can engage the average voter, whose views are more nuanced than they imagine.

Herb Stein, the famed American Enterprise Institute economist, famously declared, “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.” USPS had a 250th birthday, but absent action it is highly unlikely to survive to see its 255th.

Kevin R. Kosar is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and edits UnderstandingCongress.org. Follow him on X at @kevinrkosar.