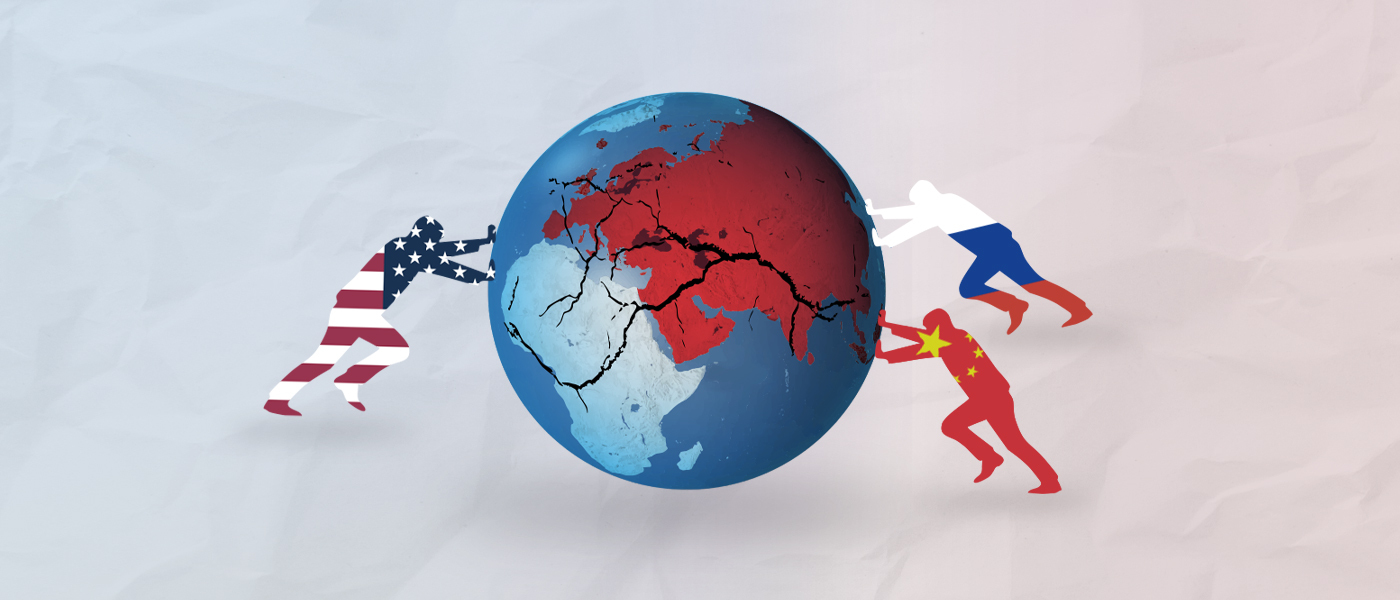

History’s Revenge: America Faces the New Eurasian Threat

The return of history was the last thing Washington wanted.

February 5, 2025This essay is excerpted from The Eurasian Century: Hot Wars, Cold Wars, and the Making of the Modern World (W.W. Norton and Company, February 2025).

The post-Cold War era wasn’t supposed to end like this. The payoff from the free world’s victory in the superpower struggle was an imbalance of power more marked than anything since the Pax Romana. America’s goal, for the next quarter-century, was to make that moment last.

The end of the Cold War transformed the international landscape: subtracting one superpower from a two-superpower system left a single, hyper-dominant coalition. America and its treaty allies accounted for roughly 70 percent of global GDP and 75 percent of world military spending. Serious competitors were nowhere to be found. China was just rising to its feet, while post-Soviet Russia was flat on its back. When another would-be challenger, Saddam Hussein, sought to master the Middle East by invading Kuwait in 1990, the resulting “mother of all battles” turned into the mother of all beat-downs, which showed how outrageously superior America’s information-age military was. The ideological mismatch was also severe; democracy, having vanquished communism, enjoyed a dearth of rivals and a surfeit of prestige.

America’s first decision, in this environment, was not to throw it all away. Neo-isolationists argued that the end of the Cold War should mean the end of US globalism; America, wrote one erstwhile hawk, could become “a normal country in a normal time.” Yet most US officials in the 1990s and later understood that America’s postwar project hadn’t been solely about containing communism. It had also involved suppressing the strategic anarchy that had ravaged Eurasia twice before. That responsibility endured, even if the Soviet Union didn’t. “Either we take hold of history,” said James Baker, “or history will take hold of us.”

The return of history was the last thing Washington wanted. So, the United States preserved its Cold War alliances as strategic circuit-breakers in key regions. It extended NATO deep into Eastern Europe, to enlarge the zone of stability that had arisen in the West. Under multiple administrations, America would maintain a globally dominant military, to keep its alliances credible and keep new threats in check. “The world order,” one Pentagon document stated, “is ultimately backed by the US”

American military hegemony would tame potential challengers until economic integration transformed them.

Sure enough, when Saddam barged into Kuwait in 1990, a US-led coalition kicked him out. When ethnic conflict engulfed the Balkans, Washington and its NATO allies extinguished the flames. When China coerced a democratizing Taiwan with missiles and military maneuvers in 1995–96, the White House sent two carrier strike groups to back Beijing down. China might be a “great military power,” said Secretary of Defense William Perry, but “the premier—the strongest—military power in the western Pacific is the United States.”

American military hegemony would tame potential challengers until economic integration transformed them. The United States welcomed China and Russia into the World Trade Organization; it pulled them into a booming global economy. This was a classic “golden fetters” strategy: it would give Moscow and Beijing stakes in supporting the US-led order, while encouraging economic reforms that would unleash pent-up desires for freedom among their people. America would turn would-be rivals into “responsible stakeholders,” and perhaps even pacific democracies, before those countries could turn against the system that had made them rich.

Finally, America would soothe the sources of international rivalry by spreading liberalism further than ever before. After 1945, Eurasia’s geopolitics changed once the politics of Germany and Japan had changed—and once cut-throat mercantilism gave way to economic collaboration. The lesson, for the post-Cold War generation, was that strengthening human rights, promoting democratic reforms from Eastern Europe to Southeast Asia, and fostering trade and globalization would bring a freer, richer, safer world. “The successor to a doctrine of containment must be a strategy of enlargement,” said Bill Clinton’s national security adviser, Tony Lake—“enlargement of the world’s free community of market democracies.”

This strategy was ambitious, but it wasn’t especially radical. In the bipolar environment of the Cold War, America had promoted security, prosperity, and democracy within the free world. In the unipolar environment of the post-Cold War era, America took that project global. The goal, George W. Bush would explain, was to “build a world where great powers compete in peace instead of continually prepare for war”—to banish Eurasian rivalry by locking in liberal values and benign US hegemony. That’s not, unfortunately, what happened—although the record of America’s post-Cold War statecraft wasn’t so bad, and the story of why it stumbled isn’t as simple as it may seem.

Consider what that project achieved. The post-Cold War era didn’t have to be a comparatively peaceful, prosperous interlude between epochs of rivalry. It might just have been more of the same. A reunified Germany and a reinvigorated Japan might have bullied the countries around them. The specter of “German aggression, German tanks,” still lingered, Polish leaders warned. The world, political scientist John Mearsheimer predicted, was headed “back to the future,” as the resumption of history freed geopolitical demons caged by the Cold War. Instead, the post-Cold War era saw rising global incomes, record levels of democracy, and another quarter-century of great-power peace. US power was indispensable in every regard.

Commerce rarely thrives in chaos. Post-Cold War globalization gained momentum in a climate of security provided by Washington, just as late nineteenth-century globalization occurred on waves Britannia ruled. US hegemony was mostly stabilizing: the extension of NATO into Eastern Europe smothered embers of conflict in that region by protecting smaller countries from their former tormentors. Germany and Japan remained within the bear-hug of US alliances that both protected and pacified them; before long, the worst one could say was that these nations spent too little on defense. And across Eurasia’s regions, it was America that deterred violent revisionism and succored emerging democracies. “Why is Europe peaceful today?” Mearsheimer later conceded. Because Washington was a “night watchman” keeping the terrors away.

So, what went wrong? One problem was the catastrophic success of economic integration. After a disastrous, post-collapse depression, Russia recovered; its real GDP doubled between 1998 and 2014, which allowed military spending to quadruple. China, now fully embarked on its post-Mao reforms, exploited global markets and technology to turbocharge development; GDP surged twelve-fold, and military spending tenfold, between 1990 and 2016. The drones, submarines, and missiles this buildup featured were often made with technology procured, licitly or illicitly, from the democratic world. None of this would have happened had Washington not pulled Russia and China into a thriving world economy—and given them the strength to unsettle the status quo.

This first problem wouldn’t have hurt so much if not for a second: democracy was less irresistible than Washington hoped. Russia never completed its political transition. The structural residue of the Soviet system, the autocratic instincts of its elites, and the economic carnage of the 1990s cast the country back into strongman rule. Autocracy persisted in China; rather than being mellowed by economic integration, the Communist Party used the resulting prosperity to buy off the population and build the repressive capabilities of the state. A thoroughly liberalized Eurasia might have become a “democratic zone of peace.” But in its two largest countries, illiberal leaders and legacies proved tenacious. Which related to a third problem: for the once-and-future great powers of Eurasia, American hegemony looked threatening indeed.

The real problem was that safety from external attack isn’t the only thing rulers want. They want glory, greatness, and empire; they want security not just for their nations but for themselves.

From the early 1990s onward, Russian leaders made clear that they didn’t welcome US influence in Eastern Europe. Russians, British diplomats reported in 1997, saw NATO enlargement as “a humiliating defeat.” Chinese officials made not-so-veiled nuclear threats when Clinton stuck up for Taiwan in 1996. Beijing would later call the post-Cold War era a “period of incessant warfare” and strife. Clearly, not everyone thought US power so benign.

But what, exactly, was so threatening? No Kremlin leader ever seriously alleged that NATO, then racing to reduce its military capabilities, was going to conquer Russia. Nor was there any chance of America invading China; if anything, the US presence in Asia made Beijing safer by precluding an unconstrained, remilitarized Japan. In some ways, Beijing and Moscow were actually the biggest beneficiaries of US strategy. China grew rich and powerful in a world pacified by Washington. NATO expansion, much as Russia hated it, kept Germany contained and Eastern Europe—long the pathway for marauding armies—tranquilized. Yes, Moscow had lost its empire. But it had gained greater safety—more than in 1914 or 1941, certainly—from external attack.

The real problem was that safety from external attack isn’t the only thing rulers want. They want glory, greatness, and empire; they want security not just for their nations but for themselves. This is where the conflict emerged.

By maintaining, even expanding, its sphere of influence, Washington was preventing Moscow and Beijing from creating their own. NATO expansion reduced the odds that a resurgent Russia might someday rebuild its empire. “Just give Europe to Russia,” President Boris Yeltsin asked Clinton. “I don’t think the Europeans would like this very much,” Clinton replied. China, once Asia’s premier power, couldn’t even take Taiwan, with the US Navy parked off its coast. The post-Cold War order might have given Russia and China what they needed. It certainly didn’t give them what they desired.

That order also antagonized China, and later Russia, by menacing their regimes. The men who ran the Chinese Communist Party were not stupid. They knew Washington was using economic seduction to promote political evolution; they worried that an autocratic regime might not survive in a democratizing world. America, Chinese officials alleged, was waging a “smokeless World War III” against Beijing. Similarly, once Russia’s democratic experiment failed, an increasingly illiberal Vladimir Putin had to fear ideological contagion from post-Soviet states, such as Ukraine and Georgia, that were reforming and moving toward the West. “We should do everything necessary so that nothing similar ever happens in Russia,” he remarked. For the advanced democracies, US influence was mostly reassuring. For autocracies, it was an existential threat.

Since US policies generated more resistance than expected, preserving the peace would have taken more effort than Washington had planned to exert. Here, a final problem arose: America wanted all good things at once.

The United States claimed a “peace dividend” even as it increased its global ambition: defense spending fell from 6 percent of GDP in the 1980s to 3 percent as the 1990s ended. That didn’t matter much at first, because America’s lead seemed insurmountable. But as the balance shifted, Washington found itself distracted and demoralized.

The distraction came after September 11, 2001. Those attacks were a by-product of America’s effort to secure the Middle East by stationing troops in Saudi Arabia—which was a grievous insult to Osama bin Laden and his fanatical followers. The US response to 9/11 was to seek a deeper peace in this least stable part of Eurasia by eliminating threats—from terrorists and rogue regimes—and implanting liberal values. Very little went as planned.

Two long, mismanaged wars claimed over 7,000 American lives. They consumed US resources for more than a decade. Their disappointing outcomes, combined with the effects of the 2008 financial crisis, produced sharp cuts in US defense spending. They also elicited a feeling, under both Barack Obama and Donald Trump, that “nation-building here at home” should displace order-building abroad. America was feeling that old temptation of retrenchment. The handcuffs on history were being loosened just as fierce Eurasian forces were stirring, again.