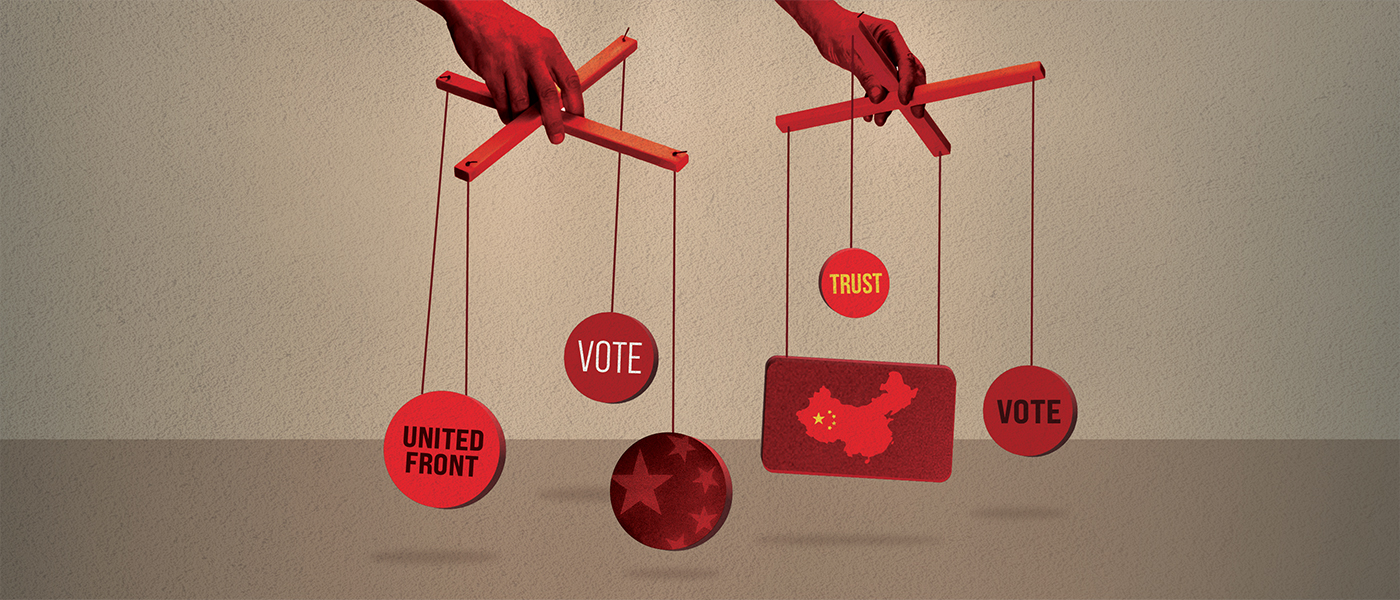

Beijing’s Foreign Influence Activities Threaten National Security and Democratic Values

China’s foreign influence efforts fundamentally threaten not just US national security but also the healthy functioning of US democracy.

As the 2025 New York City mayoral race heated up, front-runner candidate and former New York governor Andrew Cuomo recently appointed a relative newcomer with ties to the Chinese government and Beijing’s foreign influence apparatus as his Asian community liaison. This was just the latest in a repeating pattern across the United States of individuals linked to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) serving as political aides, fundraising and networking with national and local politicians, and even running as candidates and getting elected into office.

Taken together, these incidents embody the long-standing yet evolving tactics of Beijing’s malign influence and political interference in democratic societies. Alongside classic examples of blatant espionage and transnational repression tactics often used by authoritarian regimes abroad, the Chinese government is also actively trying to reshape the political landscape from the ground up. The modes and methods of China’s foreign influence efforts fundamentally threaten not just US national security but also the healthy functioning of US democracy and the rights and liberties of ethnic Chinese communities.

Many of these activities fall under the umbrella of a CCP organ known as the United Front. The United Front can be thought of as a diffuse system comprising official, quasi-official, and grassroots organizations linked together by a shared organizing principle—to promote Beijing’s interests, co-opt allies at home and abroad, and suppress regime critics. In addition to seeking to influence foreign decisionmakers, the Chinese government also prioritizes shaping—or controlling—the views and behavior of overseas Chinese communities. United Front work draws on multiple arms of the Party-state, ranging from state security (China’s civilian intelligence agency) and foreign affairs to education and propaganda. Embassies and consulates abroad help to coordinate these activities and certainly play an active role in reaching out, managing, and intervening in overseas Chinese communities.

Chinese leader Xi Jinping has articulated ambitious concepts of Great Overseas Chinese Affairs (da qiaowu) and Great United Front Work (da tongzhan gongzuo), underlining the Party’s renewed emphasis on using these instruments of influence to safeguard China’s increasingly expansive view of national security across multiple domains and assert Beijing’s clout globally. Xi himself has added a more overtly geopolitical and ideological bent to managing the overseas Chinese. He describes Chinese culture as the “common spiritual gene of Chinese sons and daughters,” with unification of the Chinese nation as a shared root for ethnic Chinese abroad and the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation as a shared dream. In other words, overseas Chinese are seen as playing an important role in achieving strategic goals such as the “China Dream” and “telling China’s story well.”

Patronage politics make fertile ground for foreign influence.

The United Front has developed a sophisticated strategy of influence that rests less on overtly pro-CCP positions and more on tailored appeals to local contexts. A 2009 article by the then-director of the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office explicitly mentioned getting overseas Chinese to participate in politics and make their voices heard, ostensibly to benefit minority group rights and promote harmony and stability in host societies. As I have written elsewhere, the Chinese government does not hesitate to play identity politics and exploit contentious social and political issues—such as anti-Asian hate, public safety, homeless shelters, or affirmative action and standardized testing—in order to gain currency among overseas Chinese populations and legitimize CCP-linked individuals and organizations as grassroots leaders defending the community’s interests and rights. This goes hand in hand with propaganda messaging of longstanding racial discrimination against ethnic Chinese and Asian Americans (as well as touting the flaws of democracies). Such mobilization in turn serves as a foundation for Beijing’s political machine to field preferred candidates and rally votes to get them elected. This means that United Front actors are not just rubbing shoulders with people in power but also getting into power.

Patronage politics make fertile ground for foreign influence. Especially in areas with large ethnic Chinese populations, politicians seeking election are eager to tap on Chinatown networks to secure votes. This leads to a reliance on political fixers and community liaisons, who by nature of their position as a community leader also often have close ties to the Chinese government. In some cases, politicians may know relatively little—or exercise willful ignorance—about the role of the United Front in local politics. Yet these activities have been going on for a long time. As one example, in the greater Los Angeles area, an overseas Chinese elite jockeying for community leader status almost two decades ago was recently sentenced as an agent of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and also worked closely with another alleged PRC agent to influence local politics. Many of these individuals hold positions in recognized United Front organizations and frequently meet with CCP officials.

Many governments seek to engage with their diaspora populations in various ways that serve their strategic goals, whether for electoral benefits back home, lobbying efforts abroad, or encouraging investments and remittances for economic growth. But Beijing is trying to exert influence—or control—through subversive ways that stamp out viewpoints different from the CCP. Moreover, the Chinese government has an exclusionary view of what being Chinese means, equating ethnicity and culture with national identity and regime loyalty. Policy discourse often does not distinguish between Chinese nationals living abroad and those of ethnic Chinese descent who are citizens of other countries. Such a view threatens the individual and civil liberties of ethnic Chinese who are unable to claim pride in their cultural heritage, maintain familial and social ties independent of having to profess loyalty to the CCP, or at minimum operate in political contexts that demand some level of complicity with Beijing’s interests. Additionally, the CCP quickly rebuts any criticism of the regime’s policies or Western fears of foreign interference as racist. This narrative weaponizes racism and undermines the legitimacy of discrimination issues faced by minority groups.

A key policy challenge is identifying who is part of the United Front. By design, the United Front blurs the lines between overtly illegal and legal, or malign versus legitimate activities. While there are core semi-official societal organizations with branches worldwide, such as the Councils for the Promotion of the Peaceful Reunification of China, Overseas Friendship Associations, and Western Returned Scholars Association, much United Front activity also involves the co-optation of overseas Chinese elites and organizations. These grassroots associations wear dual hats—providing public goods and social services needed by the overseas Chinese community while also sometimes participating in pro-China and CCP-endorsed events. Attending an anti-Taiwan protest or waving flags to welcome President Xi’s visit to San Francisco does not necessarily mean that person is a CCP acolyte—they may have been paid to come or view it as a social event. Shaking hands with a PRC consul-general may reflect a desire to gain political connections and expand personal business or career opportunities. At the same time, it is hard for overseas Chinese elites to claim complete ignorance of potential CCP leverage given their required familiarity with the political system—there is no free lunch. Chinese writings on United Front work discuss the need to align multiple incentives so that overseas Chinese can be co-opted to promote Beijing’s goals.

Certain activities are clearly past the red line, such as stealing intellectual property, taking orders from and reporting information back to CCP officials, and intimidating and harassing critics of Beijing. But United Front work goes beyond the formal recruitment of spies and agents to broader efforts to alter the beliefs and behavior of these communities and the social and political landscape in line with China’s interests and goals.

While the CCP may aspire to implement a Marxist-Leninist style “whole-of-society” approach in its foreign influence efforts, the US and other governments should not respond with a “whole-of-society” mindset. Overreaction will only add more fuel to the fire, lend credence to Beijing’s narratives of Western discrimination, and push the overseas Chinese community into CCP arms. While Chinese espionage is a real and valid concern, the recent State Department announcement to “aggressively” revoke visas of Chinese students without clearly specified criteria rings xenophobic and risks throwing the baby out with the bathwater—it undercuts the longstanding appeal of the United States as a free, open, and innovative society, which has in fact attracted many Chinese students to leave China and study and work in America. Rather, we need informed scrutiny and targeted restrictions against individuals who pose concrete national security risks.

US national security is threatened by malign influence, but so are the voices and rights of Chinese Americans and Americans writ large.

To counter China, we should not become like China. A more sustainable and clear-eyed policy approach should focus on bolstering America’s own capabilities to combat authoritarian influence. This includes more rather than fewer government resources to study and respond to these issues in a cross-agency, nonpartisan manner—the recent shuttering of the FBI’s foreign influence task force, along with an office at the State Department that studied foreign disinformation and interference, represent unfortunate developments in the reverse direction. Moreover, reducing Chinese influence on the ground requires empowering alternative legitimate voices in the form of grassroots organizations and community resources that are responsive to local needs and interests, so that CCP voices are not able to dominate the societal and political landscape or claim to represent the entire Chinese American—and even Asian American—communities.

The adage “sunlight is the best disinfectant” remains true. Transparency is needed on who the Chinese embassy and consulates are meeting with, who is hosting visiting Chinese government delegations, and who is involved in political activities. Tracing the activities of one individual can reveal a sprawling network. Association does not necessarily mean guilt—and at times it can reflect alliances of convenience rather than true loyalty—but it provides a baseline understanding of potential channels of foreign influence. To avoid becoming Manchurian candidates, politicians at the local and national levels should be more proactive in seeking information about the backgrounds of community leaders and organizations and engaging with a broad array of community representatives and viewpoints rather than just taking the easy route and listening to the loudest voice (or the one promising the most votes). US national security is threatened by malign influence, but so are the voices and rights of Chinese Americans and Americans writ large.