Displacement by Design

How bad policy made housing scarce—and how we can fix it.

May 7, 2025How bad policy made housing scarce—and how we can fix it.

Musical chairs is one of the first games we play as children. The rules are simple: there are fewer chairs than players. When the music stops, someone ends up standing. Not necessarily because they weren’t fast enough—but because the game was designed for someone to lose.

Now imagine blaming the child for losing. We question their decisions, analyze their behavior, and scrutinize their worth. We do everything except name the obvious: There weren’t enough chairs. This reflects the current approach to American housing policy.

We treat homelessness as a personal failure—an individual’s bad choice, not a system’s bad design. Across cities and suburbs, bad policies artificially limit how much housing the market can build.

Zoning and land use laws backed by the federal government in the 1920s created exclusionary housing patterns, rules, and policies to keep the lower class out of upper-class neighborhoods. Later, the rise of discretionary permitting in the 1950s and the layering on of environmental regulations in the 1970s gave local opponents even more tools to block housing. Over time, these mechanisms have been weaponized to restrict supply, delay projects, and drive up costs, making buildable land scarce and homebuilding prohibitively expensive. The result is locked-in scarcity and ever-rising prices.

When we don’t build enough housing, costs rise faster than incomes—and the longer this persists, the more unaffordable a metro becomes. Eventually, some are forced to the periphery; others are pushed into shelters or onto sidewalks.

Los Angeles offers a stark case study of how scarcity becomes policy. Attainable housing has become an endangered species. Dominated by single-family detached zoning, Los Angeles has built just 19,000 new single-family houses since 2014—many of them luxury “McMansions.” This is a drop in the bucket for a county with 3.7 million housing units. The result is a slight population decline and, tragically, a surge in homelessness.

The numbers tell the story: The median value of a single-family detached home built after 1999 in Los Angeles is around $1.5 million, well above the $875,000 median value of homes sold in 2024. Meanwhile, the average local worker earns just $50,000 per year. It’s no surprise, then, that the limited housing available is far out of reach for most residents.

This shows that homelessness in California isn’t a result of migration due to its attractive climate. It’s the product of internal, structural displacement stemming from a lack of housing construction.

At the extreme, California’s housing scarcity manifests itself with residents sleeping in parks. According to the California Statewide Study of People Experiencing Homelessness, 90 percent of California’s homeless population lost their housing in California, and 75 percent were displaced within the same county. This shows that homelessness in California isn’t a result of migration due to its attractive climate. It’s the product of internal, structural displacement stemming from a lack of housing construction.

Rather than addressing the housing shortage directly, Los Angeles relied on two main approaches—neither of which has meaningfully reduced homelessness over the long-term. The city invested heavily in low- or no-barrier supportive housing and expanded shelter systems—including sanctioned encampment sites and temporary housing—often paired with enforcement policies that pressure individuals to accept these limited options. Both pathways perpetuate a doom loop, spending progressively more without delivering housing solutions.

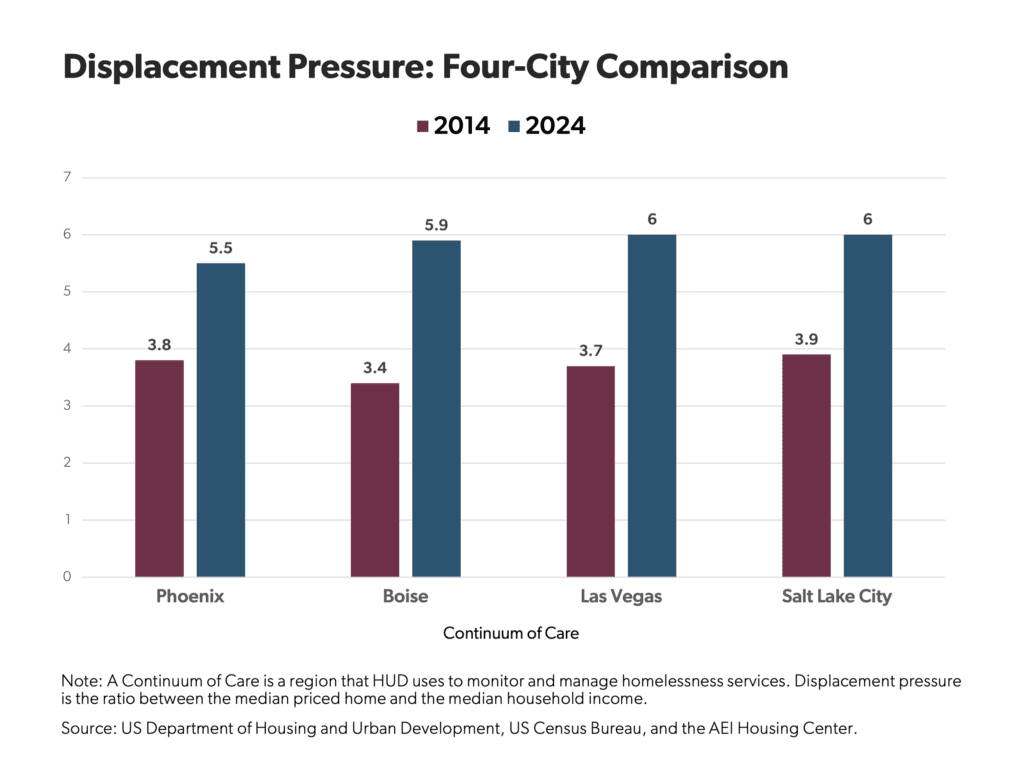

This pattern isn’t unique to California—it plays out wherever housing supply is constrained and demand goes unmet. But California’s crisis hasn’t stayed within its borders. As housing pressures have mounted, the state has for decades exported scarcity through outward migration into the “California Blast Zone”—Washington, Oregon, Arizona, Nevada, Idaho, Utah, and Texas. Californians didn’t just bring their suitcases; they brought their purchasing power and housing demand. And the pressure on home prices followed.

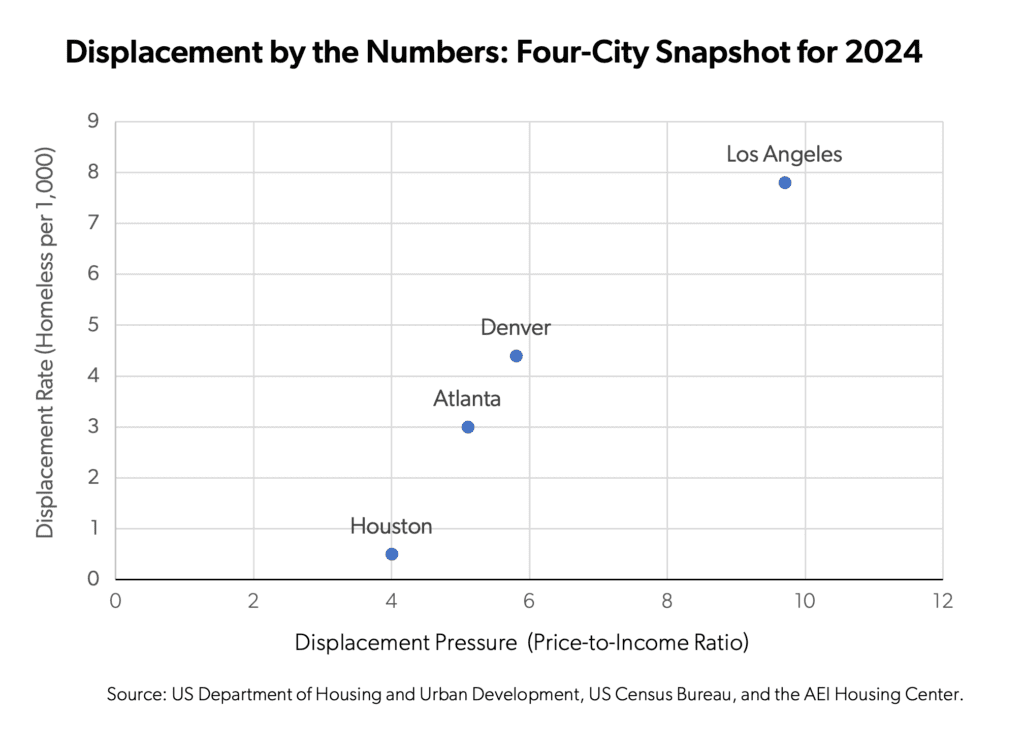

Research done by the AEI Housing Center clearly shows a trend between displacement, measured as the rate of homelessness per 1,000 people, and housing pressure, measured as the ratio between the median priced home and the median household income. We call this relationship the Good Neighbors Index (GNI). The more income it takes to afford a home, the more unaffordable a city and the greater the housing shortage.

When the home price-to-income ratio rises above 7.0, displacement rates can quadruple. Where it stays near 3.0, displacement becomes rare. A snapshot of several cities illustrates this trend.

These outcomes aren’t inevitable—they are the result of policy choices. Houston’s example shows what happens when we build enough chairs and pair supply with a smart, coordinated policy approach.

In 2011, faced with what it deemed unacceptably high levels of homelessness but constrained by limited financial resources, the city got creative. It launched “The Way Home,” a program that placed housing at the center of its strategy. Rather than relying on fragmented efforts, the initiative created a coalition of more than 100 service providers, aligning scarce resources and prioritizing rapid rehousing as the most effective intervention.

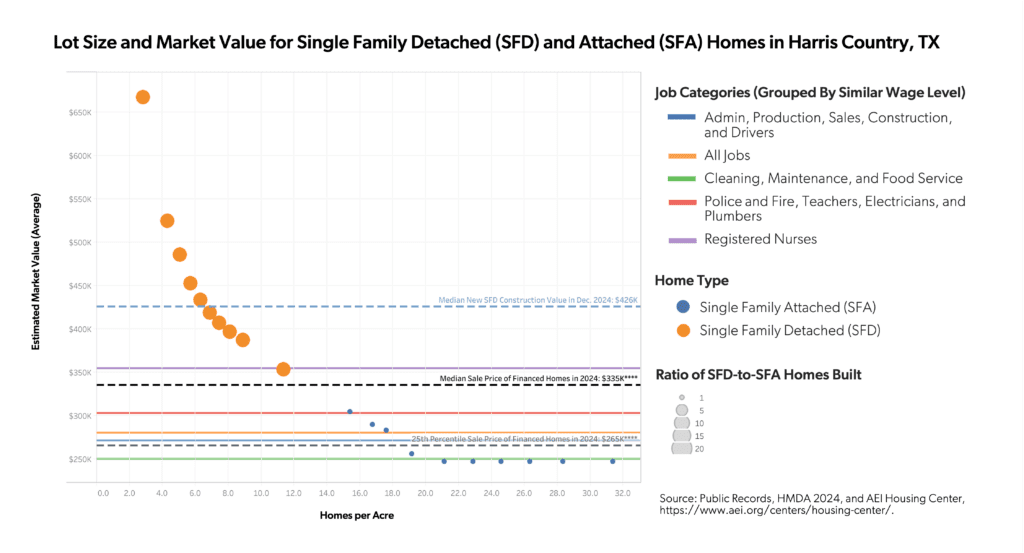

At the same time, Houston addressed the supply side of the equation. In 2013, the city expanded citywide its earlier 1998 decision to roll back restrictive land-use rules by lowering the minimum lot size requirement from 5,000 to 1,400 square feet—a move that unleashed private-sector activity and encouraged infill development. Since 2000, Houston has increased its housing stock by nearly 30 percent, supporting strong population growth while keeping housing pressures—and displacement—largely in check. Thanks to these efforts, Houston is the most affordable large city in the US.

When new single-family homes are built on smaller lots, prices tend to fall because home sizes typically scale down in proportion to lot size—creating lower-cost options compared to larger homes on larger lots in the same neighborhood. In Houston, even relatively new homes can often be found for under $350,000. This approach expands access to homeownership for middle- and working-class households—groups that are otherwise priced out.

This not only addresses immediate affordability, but also triggers “filtering”—the natural process where higher-income families move into newer homes, freeing up older, more affordable units for others further down the income ladder. It’s the same dynamic that keeps both the new and used car markets functioning effectively: Each new addition at the top of the market expands availability and affordability throughout the system. The data confirm the results. Over the past decade, Houston’s displacement rate declined—even as its population grew—while Los Angeles’s rate doubled. Today, Houston’s displacement rate is approximately one-fifteenth of Los Angeles’s.

Being a Good Neighbor begins with a mindset shift from managing homelessness to preventing it through a sense of belonging, agency, and housing abundance. It’s a community-first framework that treats neighbors as assets—not problems to be solved.

Houston’s approach to land use offers compelling evidence that liberalized zoning and abundant housing supply can achieve two critical outcomes: greater affordability and significantly lower rates of homelessness and displacement. Crucially, Houston accomplished this not through massive new government spending but by working with existing resources and strategically harnessing the strengths of the nonprofit, and especially the for-profit sectors.

Notes: From 2000 to 2024, there were 378,000 new SFD and 50,000 new SFA homes built in Harris County, TX, which includes Houston city. We set a lower bound on the estimated market value, which reflects the estimated minimally feasible home sale price given the subject county’s median construction cost, assuming a 15% land share. Each dot represents one-tenth (decile) of either SFD or SFA sales. Market value and homes per acre are averages within each SFD or SFA decile. Results are based on a regression analysis that analyzes how the market value varies for SFD or SFA homes, taking into account lot size while controlling for census tract-level specific influences, such as land values. This approach illustrates the hypothetical influence that legalizing different home type and lot size variations would have on SFD and SFA home affordability. Data for the sale price of financed homes in 2024 are limited to originated purchase loans for first-lien mortgages on new and existing homes. Source: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council and AEI Housing Center.

Based on policies implemented by Houston and other communities that have successfully lowered displacement, we distill the Good Neighbors Success Sequence (GNSS)—a market-based framework designed to reduce housing pressure, lower displacement, and make chronic homelessness rare. Being a Good Neighbor begins with a mindset shift from managing homelessness to preventing it through a sense of belonging, agency, and housing abundance. It’s a community-first framework that treats neighbors as assets—not problems to be solved.

The GNSS formula consists of five parts.

Love thy neighbor

Policy starts with people. Strong communities are founded on faith, trust, and local action—not regulation alone. Addressing homelessness calls for a more effective and humane approach that reshapes the narrative. Homelessness is not a moral failure. It’s a systemic design failure. It’s not inevitable—it’s the predictable result of exclusionary zoning, regulatory bottlenecks, and fragmented local responses. But what poor policy created, smart policy can solve.

Increase individual agency through life-navigation coaching

Rather than making decisions for displaced neighbors, GNSS calls for equipping them with smart goals, behavioral coaching, and self-determined reentry pathways. This approach fosters personal agency and sustainable outcomes, recognizing that people are more likely to succeed when they are active participants in their own journey.

Legalize the Housing Abundance Success Sequence

The three-part sequence consists of making home building by-right, rather than subject to lengthy discretionary reviews. It includes enabling smaller lot sizes in new greenfield developments; legalizing accessory dwelling units (ADUs), duplexes, townhomes, and small multiunit housing within established neighborhoods; and applying the KISS (Keep it short and simple) principle to allow faster permitting, lower construction costs, and the participation of smaller builders. This approach unlocks more housing at moderate price points. Each new unit initiates “filtering”—the essential process by which higher-income households move into newer homes, freeing up older, more affordable units for others. This dynamic mirrors the way healthy new and used car markets function.

Resource rehousing systems

Rapid rehousing programs should be funded through a combination of shallow vouchers, housing-entry grants, and localized case management. As one of the most cost-effective strategies for preventing chronic homelessness, rapid rehousing typically costs about 40 percent of the cost of services associated with long-term unsheltered living. Its effectiveness lies in getting people into stable housing quickly, where supportive services can be delivered more effectively.

Establish mutual accountability

Addressing homelessness and housing scarcity is not the responsibility of any one group alone—it requires a shared commitment. The responsibility belongs to everyone: neighbors, institutions, service providers, and local leaders. Sustainable solutions emerge when all parties are engaged, aligned, and accountable.

GNSS emphasizes that narratives erasing personal responsibility are as damaging as policies erasing human dignity. The solution lies in a balance between accountability with empathy and autonomy with support. GNSS represents a compassionate conservative response to homelessness—one that leverages the power of markets alongside the enduring strength of faith, family, and friendship. As Houston has demonstrated, this is not just theory—it’s a proven, community-centered solution that delivers real results by putting individual agency and local action at the heart of housing stability.

If, for example, a grandmother is priced out of her home, should she sleep in a tent—or live in an ADU or granny flat in the neighborhood where she helped raise her family?

The question isn’t “Who belongs here?” It’s “Have we built enough chairs for everyone to sit?” The answer isn’t about her morality. It’s about the missing housing supply.

The urgency is only growing because housing pressure, once confined to the coasts, has now moved inland. Affordable havens, like Phoenix, Boise, Las Vegas, and Salt Lake City are now experiencing the high housing pressure that eventually breaks systems of care, erodes public trust, and places massive strain on local resources.

The warning lights are flashing. Home prices and rents remain elevated. Rising delinquency rates on mortgages, credit cards, and car loans signal that many households are tapped out after years of inflation. With unemployment at 4 percent, even a modest rise could push many more families to the brink.

That’s why the AEI Housing Center is convening local leaders to demonstrate the merits of the GNSS. We are also collaborating directly with communities through AI-powered tools such as Good Neighbors AI, which tailor the GNSS framework to local needs, combining it with real-time data to help craft a compelling, evidence-based message that helps persuade policymakers to act. Good Neighbors AI turns housing pressure data into smart strategies for zoning reform and rehousing, giving leaders actionable intelligence today for tomorrow’s needs. It’s not top-down intervention; it’s bottom-up intelligence.

Everywhere we look, the message is clear: It’s time to legalize homes, care for our neighbors, and return housing to its rightful role of providing a foundation for opportunity. Let’s build enough chairs.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this work are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the official positions of the American Enterprise Institute. Ethan Frizzell writes based on his research, experience, and service in faith-based human services in Florida. All viewpoints expressed are the authors’.