The Russian Paradox: So Much Education, So Little Human Capital

Russia does not possess the economic potential one would expect of a European country of its size and educational attainment.

April 8, 2025Ever since Nobel laureate T. W. Schultz’s foundational 1960 lecture on “human capital,” economists have documented the importance of “investing in human beings” and the crucial role that education plays in economic development.

Higher levels of educational attainment are associated with better health and lower mortality for both adults and children globally, even in countries where income levels remain relatively low. Further, education’s productivity-enhancing properties abet the rise of “service economies” and “knowledge economies.” Education, and the human capital it creates, lies at the heart of modern economic development.

Yet in Russia today, we see an exception to the seemingly global correspondence between educational attainment and human capital. Russia presents the curious counterexample of a country where high levels of education coexist with strikingly poor health profiles—where the population’s considerable schooling contributes only feebly to its “knowledge production” and skills-intensive international service sector.

This Russian paradox merits attention—and not for academic reasons alone. Understanding the economic and defense potential of this large and highly schooled population will be an increasingly pressing security question as the world heads into a second cold war.

International demographic and economic data illustrate the Russian paradox. I focus on Russian conditions on the eve of the coronavirus pandemic (i.e., circa 2019) rather than trends for the early 2020s, since the demographic and economic reverberations of the pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine severely complicate any effort to compare Russian readings with more recent soundings from other countries.

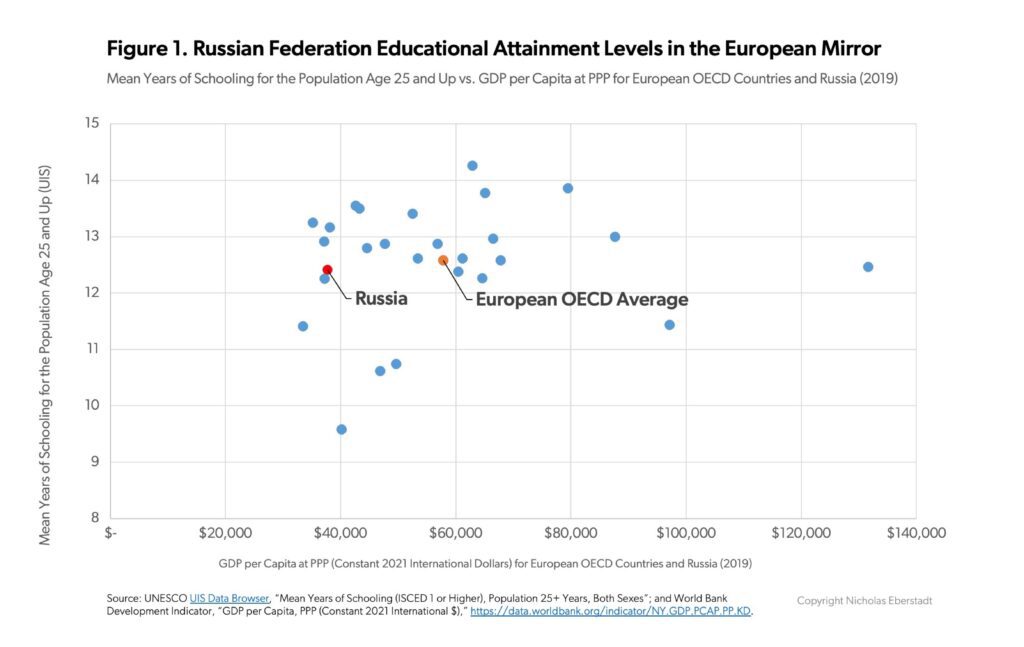

To begin: There is Russia’s level of educational attainment. The Russian Federation is a European country, and it shares important sociodemographic characteristics with other European countries. One of these is its relatively advanced educational profile, as we see in Figure 1.

According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) statistical database, Russians age 25 and older averaged 12.4 years of schooling circa 2019—almost the same as for Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Europe, which averaged 12.6 years. While some Western European countries—Germany, Iceland, Switzerland, and the UK—reported mean years of schooling (MYS) well above Russia’s, others reported lower levels than Russia: among them, Austria, Belgium, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain.

Simply put, there is nothing exceptional about Russia’s level of educational attainment from a European perspective. Russia’s adult MYS is what one would expect for a developed Western nation. It is far higher than for Russia’s BRIC counterparts: almost three years above Brazil’s, about four and a half years more than China’s; and over six years more than India’s (i.e., almost twice the Indian level). One would expect to see those sorts of differences between a developed country and less developed ones.

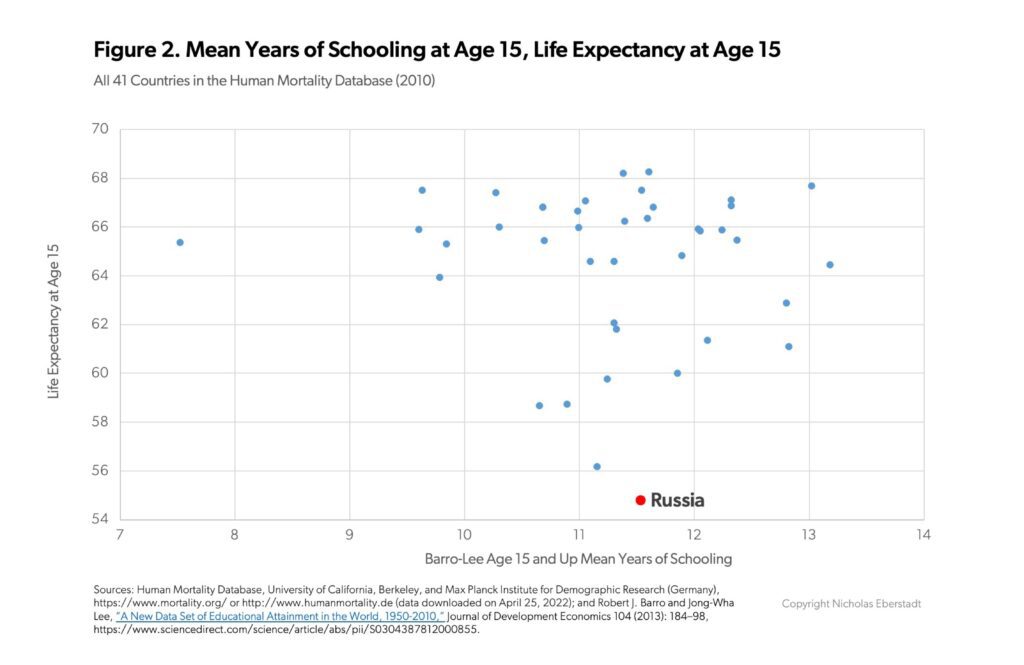

But while Russia’s educational profile looks solidly First World, its health profile assuredly does not. Take a look at Figure 2, which compares MYS at age 15 and life expectancy at age 15 for Russia and the other 40 countries included in the Human Mortality Database (HMD)—a compendium of actuarial trajectories for advanced countries with basically complete vital registration. The figures are for 2010—a good benchmark for apples-to-apples comparisons—with MYS numbers coming from the Barro-Lee Educational Attainment Dataset, a standard reference for such estimates.

Among the dozens of countries from Asia, Europe, the New World, and Oceania included in the HMD, Russia presents as the extreme outlier—with shockingly low levels of life expectancy given its level of educational attainment. According to Barro-Lee, MYS at age 15 in Australia and Russia in 2010 were basically indistinguishable, yet in that same year, combined male and female life expectancy at age 15 was almost 14 years lower for Russia. The last time life expectancy at age 15 in Australia was at Russia’s 2010 level, according to HMD, was in 1929—well before the penicillin era.

Remember: In a world undergoing a seemingly unending health revolution, yesterday’s First World records eventually become today’s Third World norms. For a country like Russia, where life expectancy at birth somehow stagnated for a full half century despite substantial health progress almost everywhere else, health levels for much of the population may not even look Third World anymore.

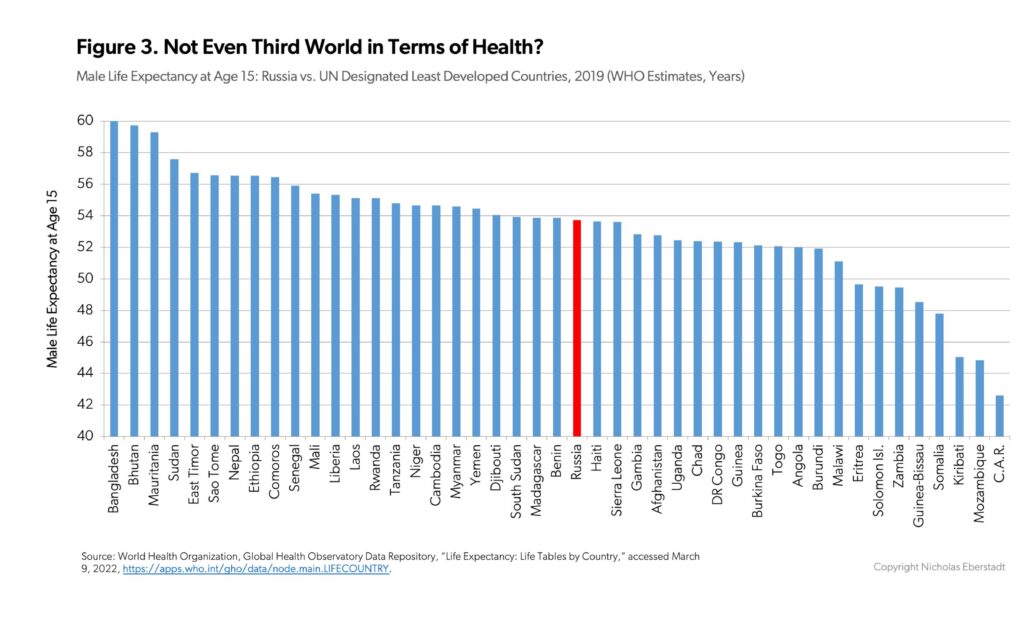

In fact, to go by global World Health Organization (WHO) “life table”–style mortality estimates, survival prospects for Russian adults on the eve of the COVID pandemic were positively Fourth World.

As of 2019, Russian male life expectancy at age 15 looks to be solidly in the middle of the range for UN’s official roster of least developed countries (LDCs)—the immiserated and fragile states designated as “the most disadvantaged and vulnerable members of the UN family.” If WHO calculations were correct, life expectancy for a young man in Russia was all but identical to that of his Haitian counterpart at that time—and practically half of the world’s LDCs in Figure 3 had higher life expectancies than Russia!

These WHO estimates further suggest that survival trajectories of Russian men were eerily close to the 2019 schedule for Africa, even though educational attainment in Russia is vastly higher than on that continent.

Russians suffer horrendous mortality from two noncommunicable causes of death. One is cardiovascular disease (CVD), including heart attacks and strokes. The other is injuries—including homicide, suicide, poisoning, and “accidents.”

Survival schedules are markedly better for Russia’s women than its men. Even so, WHO indicates that 15-year-old females in 2019 had just about the same life expectancy in Russia and Bangladesh—the latter being the healthiest country in the LDC grouping.

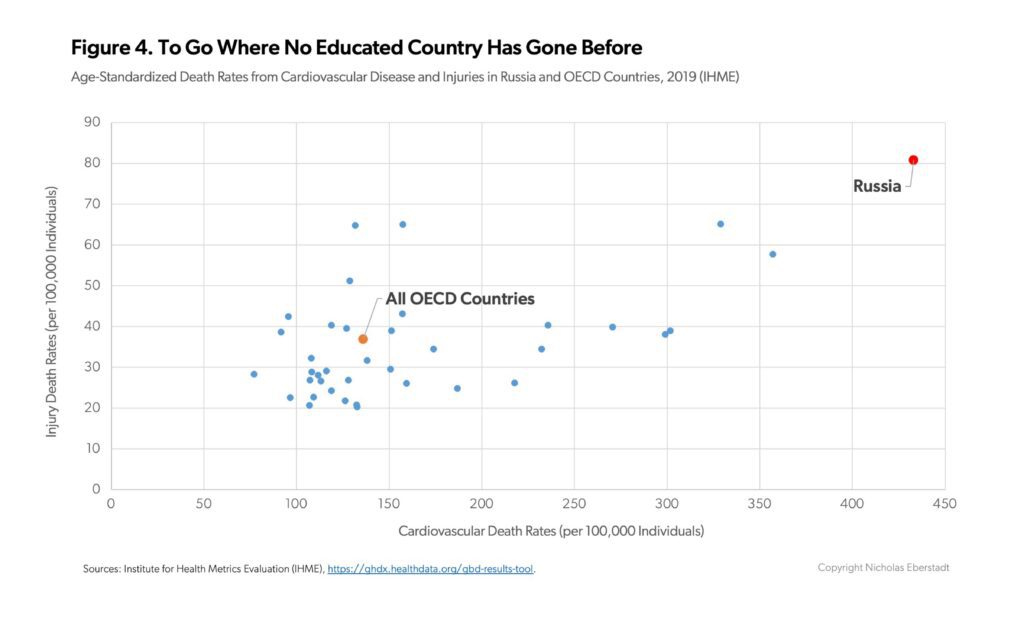

How does Russia manage to “achieve” the mortality levels of a severely impoverished society when diseases of poverty (AIDS, tuberculosis, and other communicable illnesses exacerbated by malnutrition) are no longer major killers? By pioneering new pathways to premature mortality in a highly educated population. Those grim new patterns developed under communism, but they persist in the post-Soviet era—and have yet to be cured.

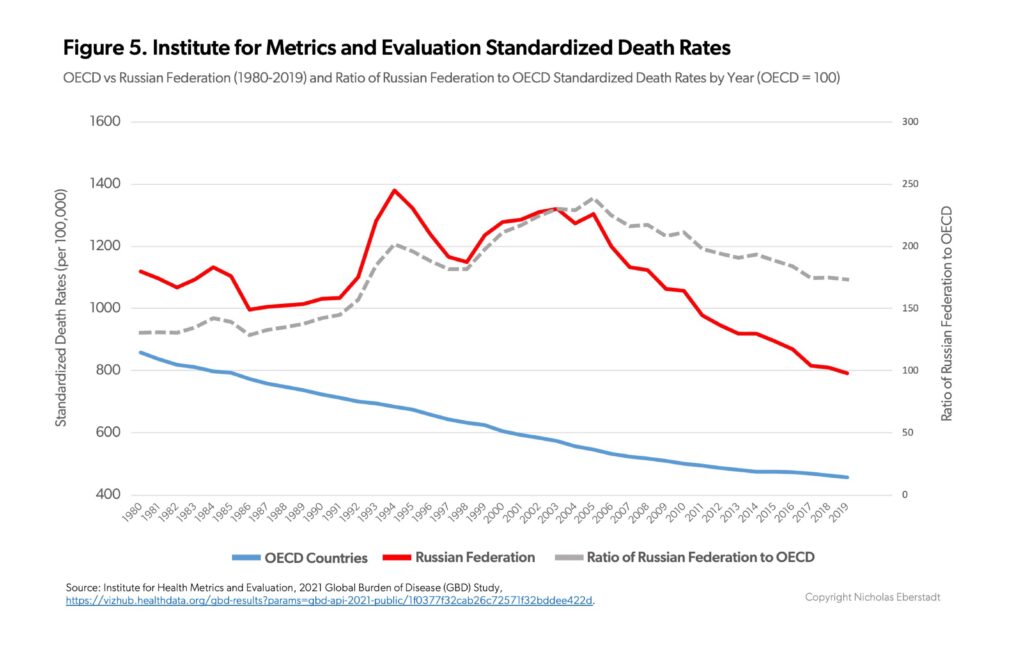

Russians suffer horrendous mortality from two noncommunicable causes of death. One is cardiovascular disease (CVD), including heart attacks and strokes. The other is injuries—including homicide, suicide, poisoning, and “accidents.” Russian death rates from CVD and injuries would be off the charts for a “normal” country with its level of education. Estimates from the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) make the point. On the eve of the COVID pandemic, Russia’s age-standardized death rates for injuries were over twice the OECD average, and mortality from CVD was nearly three times the OECD average.

By some measures, the gap in health performance between Russia and other highly educated countries is greater now than it was under communism. We can see this in Figure 5, which contrasts overage age-standardized death rates for OECD countries and Russia from 1980 to 2019. The surprising fact is that the mortality gap between the OECD and Russia, both relatively and absolutely, was actually greater in 2019—almost three decades after the USSR’s collapse—than in the late Leonid Brezhnev days of the early 1980s. Bear in mind that these standardized death rates cover the entire population, not just some especially vulnerable portion of it.

The enigma of Russian mortality—of low health in a high education society—can be identified and described, but that mystery has yet to be entirely explained. In any event, Russia has seemingly severed the link between general levels of public education and general levels of public health.

The other puzzle here concerns production and economic utilization of knowledge. By any metric one might care to use, Russia punches far below its weight.

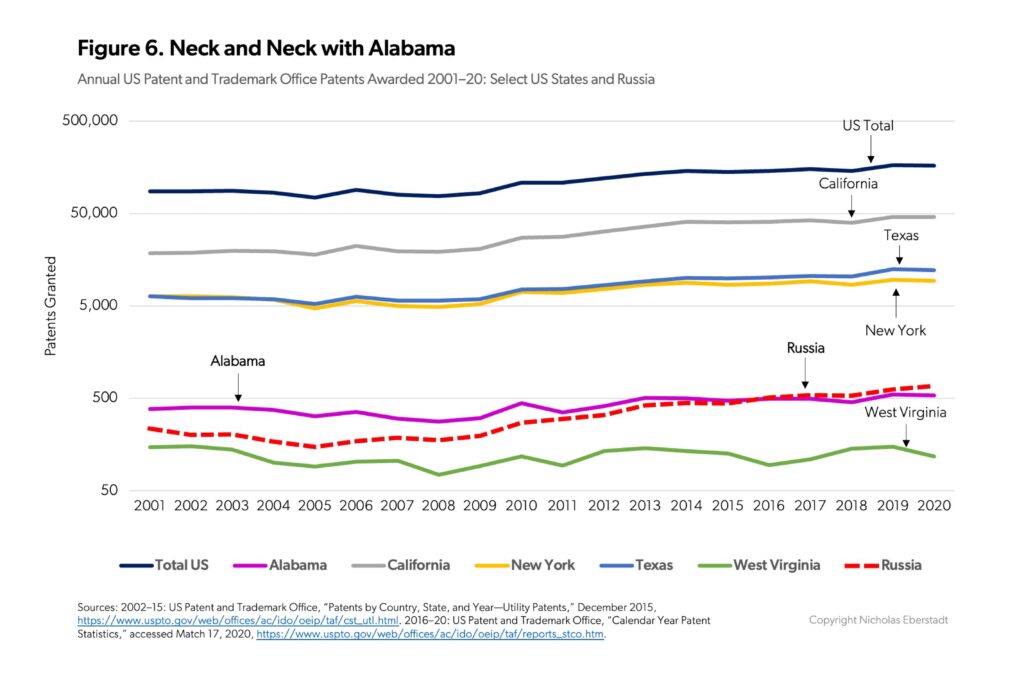

As Evan Abramsky and I noted in a 2022 monograph, Russia remains one of the “big five” globally in terms of total manpower with tertiary education. Yet between 2000 and 2020, Russia accounted for just 0.3 percent of all foreign patents awarded by the US Patent and Trade Office (USPTO). That is a miniscule fraction of India’s 2 percent or China’s 5 percent, let alone South Korea’s 10 percent or Germany’s 11 percent.

Total USPTO awards to Russia are an order of magnitude (or more) lower than for populous US states such as California, Texas, and New York. To find a peer competitor, we might look instead to a place like Alabama. Russia and Alabama ran neck and neck in USPTO awards in the years just before the pandemic (Figure 6).

Alabama has creditable research centers, of course—the Hunstville aerospace complex and the University of Alabama network among them. But Russia’s population was almost 30 times larger than Alabama’s in 2020.

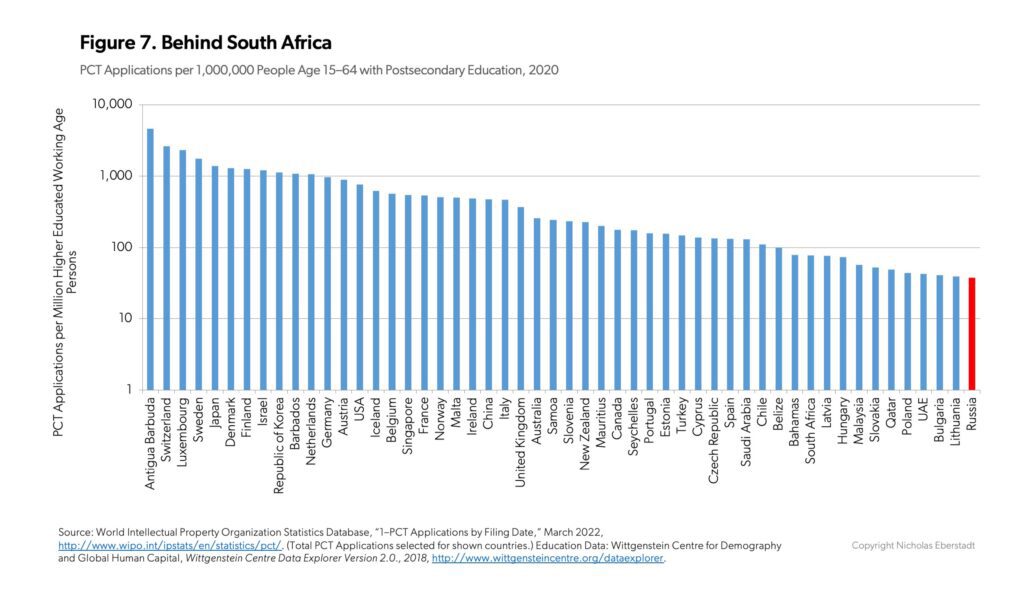

This sobering picture of Russian knowledge production is not an artifact of USPTO discrimination against inventors from Russia. It is corroborated by UN figures from their World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). According to WIPO, less than half of 1 percent of the globe’s international patent applications under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) came from Russia in 2019—a tenth of what one might have expected simply considering the size of the country’s college-trained manpower pool. In 2019, Russia ranked 22nd in PCT applications—behind places like tiny Finland and Austria.

Things look even worse when you probe further. Figure 7 displays international patent “yields” in 2019—PCT applications per million residents with tertiary education (the latter from the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Human Capital in Austria).

By this metric, Russia’s patent yield in 2020 was a 1/20th of America’s, not even 1/30th of Japan’s, and scarcely 1/70th of Switzerland’s. But those countries are international research leaders. Russia was also well behind a number of developing world “followers.” Its patent yield was barely a quarter of Turkey’s, less than a third of Saudi Arabia’s, and just half of South Africa’s. By this yardstick of patent yields, Russia ranked 52nd just before its invasion of Ukraine.

This patent Russian failure (so to speak) will leave some of us scratching our heads. Anyone who has visited Russia knows the country is full of talent. The people one meets, in my experience, are not only highly schooled; they are smart, cultivated, and intellectually accomplished. Why doesn’t this talent show up in conventional measures of knowledge production?

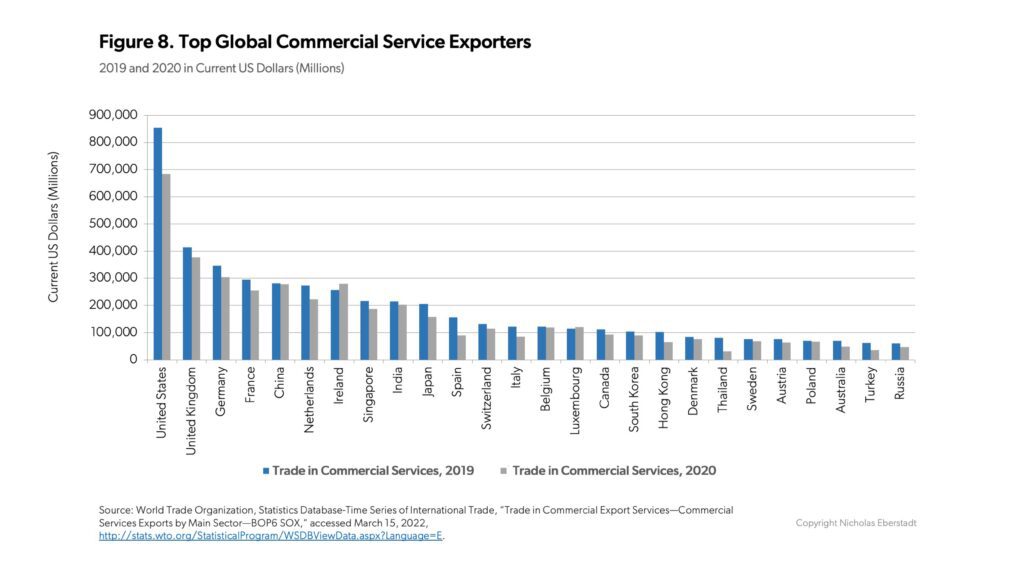

Whatever the reason, we see the same sort of problem in the pre-COVID numbers for Russian service sector exports. Unlike exports of raw materials or even industrial goods, service exports are essentially a trade in pure human capital—skills-intensive commerce in insurance, banking, and the rest. Yet in 2019, Russia—with the world’s ninth largest population and fifth largest pool of college-educated manpower—ranked 22nd in service exports—behind Denmark, Poland, and Turkey (see Figure 8).

And even in sectors where we might expect Russia to possess an advantage, the results are disappointing. In computer and information service exports, for example, Russia was 17th in 2019—far behind India and Singapore, of course, but also lagging after Poland and the Philippines.

The Russian paradox deserves much more attention from social scientists—demographers, economists, and educators—than it has to date attracted. Understanding better why such a tremendous investment in education has resulted in such meager returns in health and knowledge production is an important research question in its own right—and one with ramifications for not only Russia but global poverty reduction as well.

Meanwhile, an appreciation of the Russian paradox should also inform students of international security as they consider the ominous strategic environment emerging in the 2020s.

Under Vladimir Putin, the Kremlin’s international policy has grown ever more ambitious and assertive. Today, Moscow is engaged in a full-blown invasion of neighboring Ukraine—aided in varying degrees by its friends in China, Iran, and North Korea. We do not yet know what the Kremlin would like tomorrow to bring.

But cognizance of the Russia paradox should also serve as a cautionary tale against overestimating Moscow’s might. There is a natural tendency to do so. Russia is a large European country with a highly educated population. But it simply does not possess the economic potential one would expect of a European country of its size and educational attainment. And it is not likely to anytime soon. If anything, its potential has been reduced in recent years—not least by the brain drain of some of its finest talent, the hundreds of thousands of highly skilled young people who have emigrated since the invasion.

Underestimating a competitor or adversary can be a grievous strategic error. Overestimating one can sometimes prove no less costly.