Cancel Culture Goes Back At Least 50 Years

Edward C. Banfield questioned liberal claims about cities’ problems. Leftists and elites drove him from his academic perch.

December 5, 2025This essay is adapted from Kevin R. Kosar’s preface to The Unheavenly City Revisited, which traces problems facing America’s cities, the biases that affect policymakers’ perceptions of urban areas, and the solutions that would help people living in them.

On March 20, 1974, Edward C. Banfield took the stage at the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute. He was there to deliver a lecture, “The City and the Revolutionary Tradition,” which was one of a series of talks to commemorate the upcoming bicentennial of the American Revolution.

Banfield was a bespectacled, thin man with stooped shoulders from acute transverse myelitis, an inflammatory spinal cord disease he had contracted earlier in his life. Visiting Chicago was a bit of a homecoming for him. Banfield had earned his PhD at the University of Chicago in 1952 and been a faculty member there until 1959, before moving to Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania. His daughter graduated from the University of Chicago’s law school.

Banfield’s speech, which was later published by the American Enterprise Institute, argued that the colonial break from the British government ultimately produced a system of government that fractured power and left much of it in the hands of local governments. Furthermore, he contended that American cities were innately unruly places rocked and transformed by waves of ambitious migrants and immigrants. Boston, Chicago, New York, and other metropolises

were built by that often ludicrous and sometimes contemptible fellow—the Worshipper of the Almighty Dollar, the Go-Getter, the Businessman-Booster-Speculator—an upstart, a nobody, but shrewd, his eye on the main chance, always ready to risk his own and (preferably) someone else’s money.

Some of these individuals engaged in licit enterprises, while other men-on-the-make won their fortunes from unsavory dealings. Inevitably, these go-getters had a hand in politics and would try to advance their interests through public officials. City politics were inevitably transactional and frequently corrupt. Bribes and favoritism were coins of the realm, as mayors, aldermen, and other officials attempted to assemble coalitions to get things done.

Hence, the popular liberal notion that the federal government could make policies to remake and fix urban areas was at best overstated and at worst a pernicious myth that grossly inflated Americans’ hopes and squandered vast sums of tax dollars.

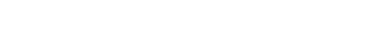

Banfield did not get to deliver a word of his lecture. Shortly after economist Milton Friedman introduced him, protesters stormed the stage, toppled the podium, and began chanting and waving a banner that read, “Racist Banfield Wanted for Genocide.” Faculty pushed back on the radicals, who were members of the Chicago Welfare Rights Organization, the Workers’ Action Movement, and other leftist groups, and demanded they leave the stage and let Banfield speak. They refused and continued their protest. After more than an hour, the event organizers decided to get Banfield out. They hustled him through the auditorium’s side door, because the main entrance was swarmed by around 90 angry protesters. “Wanted Dead or Alive Edward Banfield,” read one of their signs.

Protestors blocking Edward C. Banfield’s speech. Photo by Jack Lenahan, Chicago Sun-Times

Banfield was obviously an expert in his field. He had authored or coauthored nine books on urban politics and numerous articles for peer-reviewed scholarly journals. Nothing in his lecture dealt with or even hinted at controversial matters. So, why did protesters shout at him and stop his lecture?

The answer is that they hated Banfield’s book, The Unheavenly City: The Nature and the Future of Our Urban Crisis, which he had first published in 1970 and then revised and republished as The Unheavenly City Revisited in 1974. The book had been a bestseller (225,000 copies), and portions of it were excerpted in New York magazine and The New York Times.

Yet, The Unheavenly City made Banfield a pariah among the political left and progressive academics—and an early victim of campus cancel culture. The liberal, thought-leading New York Review of Books helped lead the charge. It published a snarling review that did not discuss the book’s substance or the extensive sociological research, ethnographic survey data, and other evidence it cited. Instead, it pilloried the man.

Professor Banfield . . . looks at poor people as essentially a different race of beings from you and me. Indeed, he writes about them as if they were strange, puzzling creatures. That poor people are people is an idea that doubtless has entered his mind, but seems in this book not to have entered his feelings.

That Banfield had served on an urban affairs task force convened by Richard Nixon’s administration was proof that he was a member of the “hard-headed,” silent majority of middle Americans who were hostile to liberal urban reforms and hopelessly retrograde.

The old American small-town myth, which Professor Banfield has put in fancy academic dress, is that if a man works hard, doesn’t throw away his life in sensuous momentary pleasures, but saves for the future, he is somehow going to get ahead to where the “best folks” live.

The review was only the beginning of a hostile onslaught from outside and inside Harvard University. A Harvard graduate student and tutor invited Professor Banfield to come for lunch not long after the book was published. When Banfield arrived, none of the undergraduate students were willing to sit at the table. Student radicals began disrupting Banfield’s classes at Harvard University.

When Banfield went on a book tour, he was greeted with disdain and tarred with calumnies. Members of Students for a Democratic Society and other leftist groups denounced him in letters to student newspapers. “Banfield is part of a racist offensive being organized by the billionaires and their politicians to keep black and white people fighting each other over a decreasing amount of crumbs,” insisted one activist. When he delivered a guest lecture on the state of American cities at Connecticut College, students argued with him, and some walked out.

The harassment at Harvard was so intense that Banfield took a position at the University of Pennsylvania. His troubles did not end. One of his tormenters followed him, enrolled as a graduate student there, and continued to stalk him.

A letter in the Daily Pennsylvanian on April 11, 1973. Tom Lanctot and Andrew Vought were students of Banfield’s.

Why did this book—“an attempt by a social scientist to think about the problems of the cities in the light of scholarly findings” with 40 pages of endnotes—provoke such rage?

In short, The Unheavenly City questioned the regnant liberal pieties of the day regarding America’s cities. The “urban crisis,” as it was so often called, was greatly overblown.

The plain fact is that the overwhelming majority of city dwellers live more comfortably and conveniently than ever before. They have more and better housing, more and better schools, more and better transportation, and so on. By any conceivable measure of material welfare the present generation of urban Americans is, on the whole, better off than any other large group of people has ever been anywhere.

Some much-decried urban problems, like traffic congestion, trash-strewn streets, and graffiti, were not matters of life and death. Yes, he explained, there were real problems, but more often than not, they were not readily solvable through government action. Rising crime, mortality, and unemployment, which were concentrated among a subset of the urban poor, flowed largely from the afflicted individuals’ values and choices.

Some individuals, for example, simply did not want to be lawfully employed. “Oh, come on. Get off that crap,” an inner-city youth replied when asked why he was jobless.

I make $40 or $50 a day selling marijuana. You want me to go down into the garment district and push one of those trucks through the street and at the end of the week take home $40 or $50 if I’m lucky? Come off it.

Indeed, some young men found that being known for brazen lawlessness raised their status among their neighbors. Taking a job for low pay (“peanuts”) or getting good grades in school invited ridicule from their peers.

Banfield insisted that class, rather than race, was essential to understanding the what and why of urban problems. And by class, he did not mean personal wealth. Rather, class meant an individual’s attitude, values, and mode of behavior, which “extends to all aspects of life: manners, consumption, child-rearing, sex,” etc.

A key differentiator among the various classes was their “psychological orientation toward the future.” Lower-class individuals were exceedingly “present-oriented” and lived moment to moment, which made them prone to self-defeating and self-damaging behaviors. They appeared to lack a sense of agency: “Things happen to him, he does not make them happen.” (Emphasis in original.)

To be clear, Banfield noted, many lower-class individuals were poor. But “lower-class” and “poor” were not synonymous. Lower-class individuals could be found at every income level. City tabloids often carried stories of uptown, adolescent wastrels who squandered their parents’ fortunes by partying nightly, buying luxury goods, and never working. Similarly, upper- and middle-class individuals could be found among cities’ most impoverished residents. They, however, were unlikely to remain poor long if schooling and jobs were available.

But the upshots of Banfield’s class-based analysis were immense. For one thing, any urban “problem” was in fact multiple problems. Take unemployment, for example. Upper-, middle-, and working-class individuals might be jobless due to a mismatch between their skills and the available jobs. They may be underemployed due to a physical disability or because they have caregiver duties to children or infirm family members. Training programs could benefit some of them, and income support payments could keep the others from destitution.

The lower class, Banfield explained, was another matter. Unemployment was their norm precisely because they were present-oriented, which made them low-skilled and undependable laborers. Banfield thought it unlikely that any policies could change these individuals’ values and enable them to take advantage of employment training or government-made jobs.

None of these observations was what activist students wanted to hear. They viewed urban problems as a product of the United States having a racist caste system dominated by corporations that wanted to oppress the poor and the non-white. They felt Banfield’s analysis was, to use a term popular at the time, “Blaming the Victim.”

A Basic Books print advertisement that Banfield sent to one of his former University of Pennsylvania students.

Radical students and liberal journal editors were not the only people Banfield offended. Academics, social reformers, and politicians who decried the urban crisis and demanded aggressive government intervention were outraged. Banfield’s gimlet-eyed assessments were a direct rebuke to this potent policy network, which had fomented the federal government’s Great Society and the preceding urban renewal policies. “If Banfield is right . . . the noblest efforts of the past thirty years have been wrong, what progress has occurred has been accidental,” wrote Richard Todd in the Atlantic Monthly.

By questioning the intellectual narrative about metropolitan life and its challenges, The Unheavenly City imperiled the political support for these reformers’ public policy experiments. “During this period of groping for . . . new solutions,” fretted Professor Robert E. Agger, “the voices of the Banfields could do damage.” The book’s analysis, he declared, was “dangerous.”

Banfield rubbed salt into the wound by credibly accusing the reformers of being blinded by their own class prejudices and moralistic zeal.

The mass movement [over recent decades] from the working into the middle class and from the lower middle into the upper middle class accounts as much as anything for the general elevation of standards that . . . makes most urban problems appear to be getting worse even when, measured by a fixed standard, they are getting better. . . .

The ascendancy of the middle and upper middle classes has increased feelings of guilt at “social failures” (that is, discrepancies between actual performance and what by the rising class standards is deemed adequate) and given rise to public rhetoric about “accepting responsibility” for ills that in some cases could not have been prevented and cannot be cured. . . .

. . . It is always society that is to blame. Society, according to this view, could solve all problems if only it tried hard enough; that a problem continues to exist is therefore proof positive of its guilt. (Emphasis in original.)

Of course, many readers did like both versions of The Unheavenly City, as its impressive sales attested. Their assessments, however, far less frequently found their way into the pages of scholarly and opinion journals, where “the small world of opinion-makers” of academics, media, and other elites held a “conventional wisdom” that he questioned.

It took a few years, but the furor around The Unheavenly City did subside. Banfield made his way back to Harvard in 1975 and finished his career there in relative peace.

Over a half century has passed since this book was published, and The Unheavenly City Revisited has been out of print since Banfield’s death in 1999. No longer is it required reading in college courses on urban politics or public policy. Tattered copies can still be found for sale online, but they have grown fewer. It is rare to meet anyone who has heard of the book who doesn’t have gray hair.

The American Enterprise Institute, where I work, aims to change all that. It has republished The Unheavenly City Revisited.

This is good news. The Unheavenly City Revisited is a wise book, and there is much to learn from it.

Most fundamentally, The Unheavenly City Revisited reminds policymakers and anyone who aspires to better the nation’s cities to be prudent. Fixing problems through government action is a value-laden and complex enterprise. Banfield’s book teaches that government officials and citizens alike must be realists about what public policy can achieve and recognize that anything they do could make matters worse.

City problems are not empirical facts; they are socially and politically constructed, and individuals will disagree on what constitutes a problem and whether it merits government action. Policymakers and elites should recognize that their technical expertise does not preclude their values from coloring their perceptions. That policymakers think something is a crisis does not necessarily make it so.

To be sure, not everyone will agree with everything in The Unheavenly City Revisited. Nor should they. Banfield never expected universal acclaim. Indeed, he anticipated that “this book will probably strike many readers as the work of an ill-tempered and mean-spirited fellow.” Unlike the radical students and various elites who tried to cancel him, however, Banfield recognized diversity of opinion as a fact of life and hallmark of a free society.

Kevin R. Kosar is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and edits UnderstandingCongress.org. Follow him on X @kevinrkosar.