Better Tools, Fewer Raids: The Digital Solution to Illegal Immigration

Improving E-Verify could create more effective immigration control.

The owner of an Omaha food packaging plant recently raided by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) claimed that his company used the federal government’s E-Verify web system to confirm that his workers were in the country legally and authorized to work. Yet roughly 70 of the 100 employees screened by ICE on the spot were taken into custody. A system that apparently falls this far short needs improvement, but the question is where to start.

To understand this challenge, it is first essential to delve into the building blocks of E-Verify, how the system is used now, and its effectiveness across the country. These components are central to examining ways to improve it and whether the system’s use by employers should be made mandatory to curb illegal immigration. A refined E-Verify system has the potential to not only help employers comply with the law but also reduce the need for expensive and difficult raids, incarcerations, and deportations.

What is E-Verify?

E-Verify is an internet-based system that compares information entered by an employer from an employee’s Employment Eligibility Verification (known as a Form I-9) to records available to the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Social Security Administration (SSA) to confirm employment eligibility. Form I-9, which has been mandatory since 1986 for new employment and recertifying expired employment authorization, requires that a new employee attest to their employer of their eligibility within three business days of hire. The employee must also present their employer with acceptable documents as evidence of identity and employment authorization. The employer must examine these documents to determine whether they reasonably appear to be genuine and relate to the employee, then record the document information on the employee’s Form I-9 and keep it on file. The form does not require a Social Security number (SSN)—which is not used on eligible documents such as a state-issued identification, driver’s license, or voter registration—and does not require a photo on all eligible documents (such as a school transcript or Social Security card).

Owing to concerns about the widespread availability of fraudulent identity documents used for the Form I-9, DHS, working with SSA, created a basic version of E-Verify in 1997 containing their combined records on individuals. Except for certain states and employer types, its use by employers is voluntary. Its use is also only permitted after an applicant accepts an offer of employment; it cannot be used to discriminate.

The system notifies the employer whether the information provided by the employee matches that of an eligible worker. If it does not match, the employee must be informed privately within 10 federal workdays and is given eight federal workdays to resolve the discrepancy before employment should be terminated. E-Verify ensures that the information a worker provides is accurate—but not necessarily that the individual is the person identified by the documents. Owing to concerns about identity theft, E-Verify includes a photo-matching tool for federally issued documents, such as passports, but not state driver’s licenses, which is a commonly presented form of identification for both legal workers and those seeking employment under stolen or false identities.

E-Verify includes a photo-matching tool for federally issued documents, such as passports, but not state driver’s licenses, which is a commonly presented form of identification for both legal workers and those seeking employment under stolen or false identities.

How Is E-Verify Used Now?

The federal government mandates the use of E-Verify for all its contractors. In 10 states—mainly in the South—E-Verify is required for all employers, at least above a certain size. Twelve more states require it for public employers and government contractors, and in one state, it is required for government contractors in certain counties and cities. Enforcement of these state mandates, particularly for private employers, is reportedly quite incomplete, and the consequences of noncompliance vary. The result is a fractured environment where many employers skirt regulations without consequence, while a few face heavy penalties or losses from their workforce.

Any other employer, such as the Nebraska food packer mentioned above, may use E-Verify voluntarily. Many large employers, particularly those operating in multiple states or with divisions receiving government contracts, do use it. States can also tack on additional requirements regarding employee notice, as California and Illinois have done. Once an employer signs up with DHS for E-Verify, it must use the system to check all new employees.

Some employers may use E-Verify as a defense in the event of ICE enforcement in order to demonstrate compliance with their Form I-9 obligation to examine proffered documents. While the law mandates the inspection of separate, typically physical, documents, studies suggest that many employers do not compare names returned by E-Verify with the information submitted by an employee, nor do they compare the photograph on the proffered document with the image returned by E-Verify to detect fraud. Other employers may use E-Verify selectively, in violation of program requirements, or encourage workers to present documents that will not trigger the photo-matching tool.

Other employers may use E-Verify selectively, in violation of program requirements, or encourage workers to present documents that will not trigger the photo-matching tool.

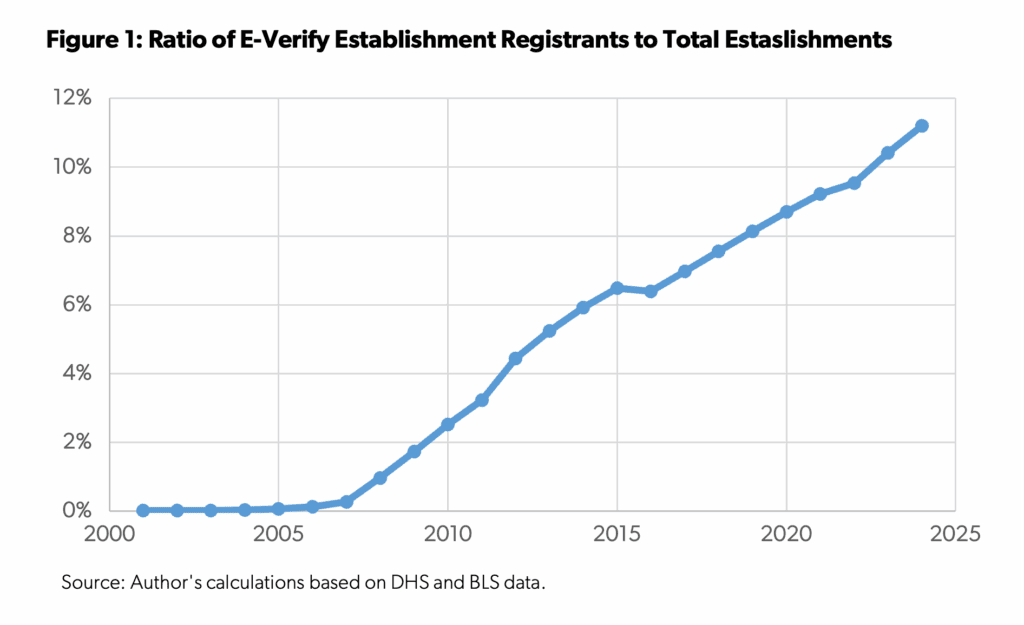

Figure 1 shows the proportion of establishment employers—both private and public—registered to use E-Verify since 2002. By 2025, nearly 1.4 million employers were participating in E-Verify, up from 265,000 in 2011. As a share of all private and public establishments, large and small, E-Verify registration rose steadily from 1.7 percent in 2009, when the federal government began requiring its use by contractors, to 11.2 percent in 2024. The top five industries—accounting for more than half of enrolled employers—are professional, scientific, and technical services; food services and drinking places; ambulatory health care services; specialty trade contractors; and administrative and support industries.

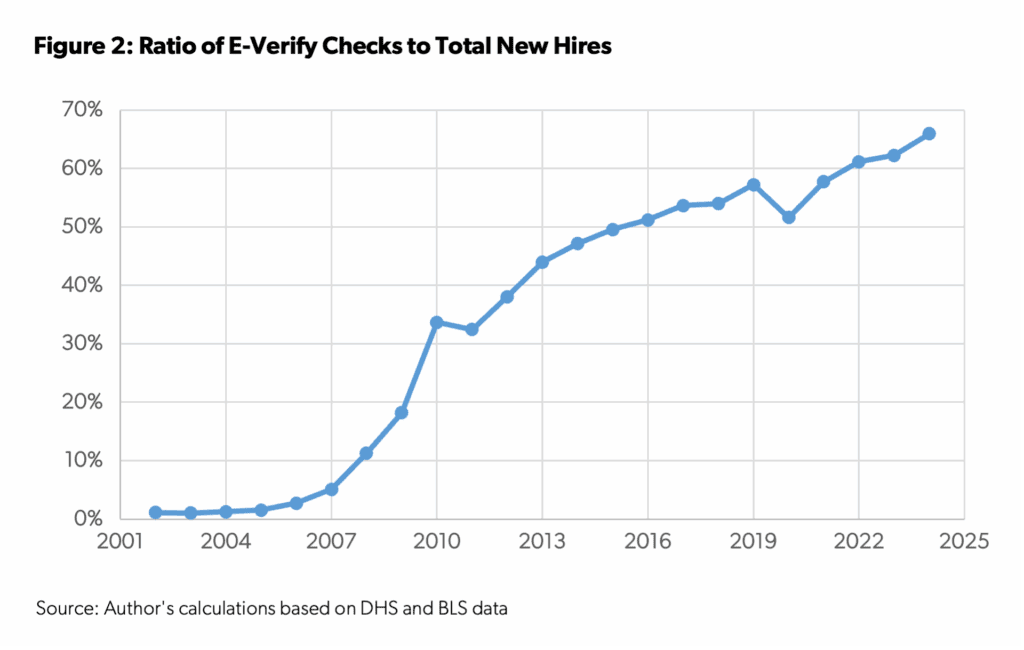

Figure 2 shows the annual proportion of E-Verify cases relative to total new hires, noting that some hires may be subject to multiple checks. Consistent with the fact that large employers are more likely to register with E-Verify than small employers, the share of new hires checked by E-Verify rose significantly from 18 percent in 2009 to 66 percent in 2024, suggesting that a full universal mandate is a plausible policy goal, albeit with a phase-in period for small establishments.

How Effective Is E-Verify?

As mentioned above, E-Verify does not guarantee that the worker is the person they claim to be. According to a 2009 study, about half of all illegal workers who were run through the system evaded detection, primarily by borrowing the identification of legal workers. It is unknown whether improvements to E-Verify since then—such as the inclusion of additional document types like US passports in the photo-matching tool—have reduced this problem, or if, conversely, identity theft has become more sophisticated over time.

Nonetheless, of the nearly 43 million cases processed by E-Verify in FY 2024, 1.51 percent were found not to be authorized for work in the US. Nearly all these cases go unresolved after the employer closes the case (presumably after the eight-day waiting period) or are uncontested. This indicates that E-Verify does have some effectiveness in identifying unauthorized workers. This no-match rate–which measures how often submitted documents do not align with the identity information on file—has remained steady for at least the last four years.

While these are indicators of the system’s effectiveness, the system is imperfect. An estimated 0.17 percent of E-Verify cases are errors, placing an administrative burden on legal workers to contact SSA or DHS after an initial no-match to resolve their authorized work status.

The gradual and incomplete introduction of state mandates for the use of E-Verify provides researchers with an opportunity to study the program’s impact on the employment and residence patterns of illegal immigrants. Researchers can scrutinize the impact across states through “difference-in-difference” analysis, which can compare states that differ in their use of E-Verify at different times.

A 2017 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas found that E-Verify reduced the number of illegal immigrant workers by between 14 to 83 percent, and illegal immigrant populations by between 10 to 70 percent, in most states mandating its use—although in two states, there was no statistically significant impact by either measure. Another study by the Dallas Fed found that E-Verify reduced earnings among likely illegal immigrants by about 8 percent, while raising earnings by approximately 7 percent among legal workers likely to compete with them. These findings are generally consistent with those of other studies using different methods, although the increase in wages among legal workers is a conclusion unique to the Dallas Fed study.

How Can E-Verify Be Improved?

Even in its partial and imperfect state, E-Verify can be effective in curbing the employment and settlement of illegal immigrants. Presumably, in a universal, mandatory, and more refined form—combined with increased enforcement of its rules by DHS or the Department of Labor—E-Verify would be significantly more effective. But it is not a panacea. The program is not designed to prevent work in the black market, self-employment, or illegal immigration involving no work activity. Still, ideas to improve E-Verify have long been a part of public discussion. According to a 2012 study, E-Verify could be improved through several changes that would empower applicants with legal work status, emphasize employers’ responsibilities, narrow the capacity for fraud, and broaden the tools available to the federal government for detecting false information.

On the employer side, steps toward improvement would include additional education and auditing of employers to ensure they properly fulfill their I-9 obligations, including careful review of proffered documents. Changes could also be made that reduce the number of documents accepted for I-9 verification and in E-Verify processes to those with strong security features and demonstrably lower risk of fraud. Job applications could require written certification from the applicant that they agree to complete an E-Verify self-check within 5 days of applying, and to resolve any discrepancies within 10 days of application. The employer’s application document (assuming there is one) might include language that explains that self-check, and that resolution of any discrepancy in the SSN or legal status is a prerequisite for employment.

Within the federal government, an advantage could be gleaned through continual analyses of SSNs used in employment verification, which could identify those that appear repeatedly within short timeframes or in multiple geographic areas—an indication of fraud. This would allow easier issuance of no-match notices on such numbers prospectively, requiring employee correction to gain work authorization. Additional statistical analyses of fraud and identity theft patterns within E-Verify could shorten employer and employee response times for cases falling into “presumed no-match” categories based on those findings. Within the DHS and SSA specifically, there should be more stringent matching algorithms in their databases to reduce tolerance for discrepancies that currently result in false positives, particularly in fields such as name, date of birth, and SSN. To avoid false no-matches, sophisticated attention to variant name spellings, hyphenations, and so on is particularly important.

Other means of improving the system would require more buy-in from states and prospective employees themselves. States, for example, could provide the E-Verify system with computer-readable driver’s license photos.

Should E-Verify Be Made Mandatory?

If a change to requiring all employers—regardless of size and sector—to use E-Verify for new hires is backed up by meaningful enforcement, levels of illegal immigration will likely decline quickly and substantially. This could, at least in part, replace the reliance on expensive, difficult, and controversial ICE raids, incarcerations, and forced deportations as the primary means of immigration enforcement. As seen in recent experiences and debates surrounding ICE enforcement, however, the negative consequences of a strict E-Verify mandate would be especially pronounced in industries such as agriculture, construction, home repairs and maintenance, food preparation, hospitality, and nursing and home care. The US labor market may be flexible enough to absorb and adjust to the change—eventually alleviating worker shortages and wage pressures through new workers coming from unemployment, retirement, or extended periods away from the labor force—or that capital and technology can be effectively and economically substituted for labor.

More likely, however, such a shift would prompt changes in immigration law and policy, such as expanding temporary work status programs, including year-round employment, or new legal pathways to permanent residence and employment for workers in high-demand sectors—particularly in light of declining domestic birth rates. That would be a welcome outcome, and help untangle the central contradictions long evident in the nation’s approach to immigration.

Mark J. Warshawsky is a senior fellow and Wilson H. Taylor Chair in Health Care and Retirement Policy at the American Enterprise Institute, where he focuses on Social Security and retirement issues, pensions, long-term care, disability insurance, and the federal budget.