Simplifying Americans’ Return to Work from Disability

Benefits should be approachable for those in need, and fair to taxpayers footing the bill.

To receive cash benefits from the Social Security Disability Insurance program and health benefits from Medicare, federal rules require that a worker must have a significant disability that prevents employment and is expected to last for at least 12 months. Moreover, the disability must be proven by extensive documentation and periods of review. Nevertheless, it is hoped that at least some recipients will recover or find accommodations that allow them to return to work, earn wages, obtain health insurance, and cease receiving government benefits. Indeed, the Social Security Administration (SSA) has established complex and extensive incentives and supports intended to encourage such transitions, benefiting disabled beneficiaries and taxpayers. Yet these incentives are incomplete and exceedingly difficult to understand. They are burdensome to administer, the supports are largely ineffective, tested policy alternatives are only modestly successful, and return to work from disability remains low, though it has increased somewhat in recent years. I propose a radical simplification that is easier to understand and administer, would likely be of modest cost to the taxpayer, and may improve the incentives to return to work.

Current Incentives

The trial work period allows a disabled worker to test their ability to work for at least nine months. During this period, they receive full Social Security benefits regardless of earnings, provided those earnings are reported and the disability continues. In 2025, a trial work month is defined as any month in which total earnings exceed $1,160. If self-employed, a trial work month is counted when earnings exceed $1,160 (after business expenses) or if the individual works more than 80 hours in their own business. The period continues until nine cumulative trial work months are used within a 60-month period. Benefits continue for a three-month grace period thereafter. Subsequently, benefits can be suspended if the worker is deemed to have “substantial” earnings. In 2025, monthly earnings over $1,620 (or $2,700 for blind beneficiaries) are considered substantial gainful earnings, as indexed and set by law. This means that in the initial trial period, a beneficiary could have substantial earnings in brief, sporadic bursts spread over many years and continue to get disability benefits. Conversely, consistent but low-wage employment—or many hours worked in their own business earning little or nothing—can exhaust the trial work period in less than a year and then be subject to benefit cessation. As a result, steady, hard-working individuals could find themselves without benefits while less consistent workers maintain them.

The complexity extends even further. After the trial work period, the disabled worker enters a 36-month extended period of eligibility, during which they can work and still receive full benefits for any month their earnings are not “substantial.” No new application or disability determination is required to receive benefits during this period. So, during this extended eligibility window, a disabled worker can get benefits—averaging $1,600 per month in 2025—and earn up to $1,620 in wages, for a combined monthly income of $3,200. This compares with about $1,260 from a full-time minimum wage job. However, if the disabled worker earns just $1 more—$1,621 in a given month—then they receive no disability benefit at all due to the “cash cliff.” Moreover, if, at the end of the 36-month period, the worker earns less than the substantial gainful amount in a given month—even after earning well above it for the prior 35 months—the period is extended month-by-month if and until the beneficiary has substantial earnings in a month. Similarly, if an attempt to work was stopped after a short time (six months or less) owing to the disability, then the job can be declared an “unsuccessful work attempt.” In that case, the earnings for that period are disregarded, and cash benefits will be paid retroactively.

However, if the disabled worker earns just $1 more—$1,621 in a given month—then they receive no disability benefit at all due to the “cash cliff.”

Even if benefits are terminated—say after four years of steady work—the worker can be reinstated and restart benefits within a five-year period if they’re unable to keep working due to their disability. They don’t need to file a new application or wait for benefits to resume while their medical condition is reviewed. Once the request is approved, an initial reinstatement period of 24 months (not necessarily consecutive) begins and ends after 24 months of payable benefits. After that, the cycle of trial work period, extended period of eligibility, and expedited reinstatement begins again, along with a new period of extended Medicare coverage.

Even during months when disability cash benefits cease due to earnings, free Medicare Part A coverage—which covers costs like hospital care—continues for at least seven years and nine months after the end of the nine-month trial work period. After that long period, the worker can buy Medicare Part A coverage by paying a monthly premium, usually at a 45 percent discount. Similar rules apply to Medicare Part B and D coverages, which cover costs like outpatient medical services and prescription drugs.

If the disabled worker needs certain items or services—such as taking a taxicab, paratransit, accessible transport vehicle, or other forms of transportation to work due to a disability—or needs to pay for counseling services in order to work, these expenses can be deducted from monthly earnings in the various calculations described above. In addition, subsidies and the extra value provided by special work conditions provided by employers or third parties are not included in countable earnings.

Supports in Place

Beyond cash benefits and health insurance, those who qualify for disability have access to other support. If a disabled worker participates in a vocational rehabilitation program, benefits can continue during participation, even if it is determined that the worker is no longer disabled. Such programs include an individualized education program, a plan for employment through a state vocational rehabilitation agency, a plan to achieve self-support approved by SSA toward a work goal, or participation in a Ticket to Work service (explained below). On top of this, advocacy agencies funded by SSA provide job assistance and a federal Job Accommodation Network provides guidance to disabled workers to enhance their employability. Each SSA office has a work incentive liaison, and SSA also funds work incentives planning and assistance projects—both designed to help disabled workers navigate incentive rules. SSA also provides the Benefit Planning Query, which gives beneficiaries and their advisers personalized information about their benefits and earnings.

The Ticket to Work program was established by 1999 legislation to expand access to vocational rehabilitation services for disabled workers. Among the program’s innovations were giving beneficiaries the choice to work with private employment networks instead of just state agencies, and adopting a performance-based model for SSA payments to service providers, which better aligns incentives toward returning beneficiaries to long-term employment. Additional features included protection from continuing disability reviews for Ticket users, extended Medicare coverage, and expedited benefit reinstatement if the work attempt failed. Yet usage of the Ticket remains relatively low, and studies have shown that the program has not significantly increased transitions off benefits or into sustained employment. As a result, this program costs more than it saves.

Alternative Policies Tested

In the past two decades, two large demonstration projects mandated by Congress tested whether altering the incentive rules increases work effort and reduces benefit receipt among disabled workers. The first, called the Benefit Offset National Demonstration (BOND), removed the cash cliff and replaced it with a $1-for-$2 offset, whereby benefits are reduced by $1 for every $2 earned above the substantial gainful activity level; all other rules remained in place. Comparing tens of thousands of disabled workers randomly assigned to treatment and control groups (the latter subject to current offset rules) over four years found no statistically significant evidence that the offset policy increased average earnings, even for a subgroup that received enhanced work incentive counseling. In contrast, the new offset policy did raise the average amount of benefits by about 1 percent.

The second project, called the Promoting Opportunity Demonstration (POD), more substantially altered the incentive rules with volunteer participants randomly assigned to three groups: the control group (current rules) and two treatment groups. The first treatment group had the cash cliff replaced with a $1-for-$2 offset for earnings above the trial work level (which would be $1,160 per month in 2025); this offset started immediately, with no trial work, grace, or extended eligibility periods, but members of this group did not ever face termination of benefits. The second treatment group had these same conditions, but faced termination of benefits after twelve consecutive months of earnings above the full offset amount (when benefits were reduced to zero). There were small positive, albeit not statistically significant, increases in average earnings, benefits, and income among the treatment groups. Both treatment groups had a statistically significant 1 percentage point increase in the share of beneficiaries earning above the annualized substantial gainful activity amount—about 10 percent more relative to the control group. There were no differences in benefit offset usage or impacts between the two treatment groups, except that more members in the first group had benefits offset for at least 12 consecutive months. Survey evidence strongly indicated that most study participants did not understand either current or treatment incentive rules, despite access to work incentive counseling.

The Actual Experience

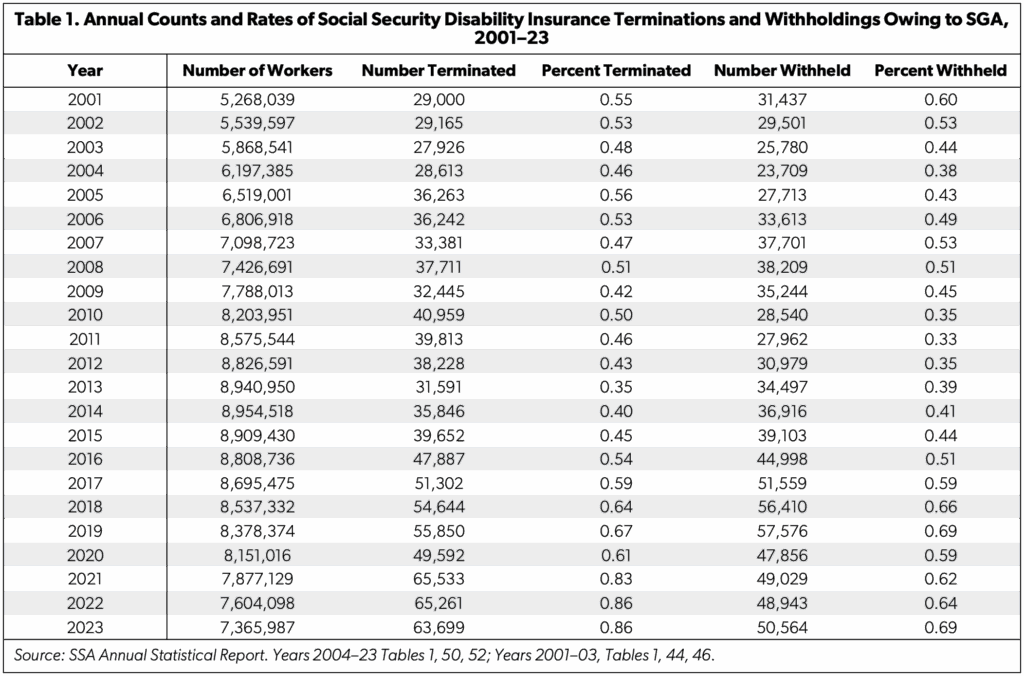

Table 1 shows percentages of disabled workers who had benefits terminated due to significant work at the substantial gainful activity (SGA) level from 2001 through 2023, as well as the percentage who had benefits ceased (withheld) as of December of those years. As noted above, the numbers are modest, with some fluctuation over the years and an increase since 2016—perhaps reflecting, with a lag, rising and falling general labor market demand, recent easing of work conditions, and possibly a pickup in SSA continuing disability reviews. The return-to-work incentive rules, last revised in 1999 and implemented thereafter, and Ticket supports, last revised in 2008, do not appear to have had a clear impact.

A Better Proposal

I recommend following the basic outline of the incentive rules used in the second treatment group of POD, but keeping and extending the trial work period to one year (with no grace period) and converting all calculations to an annual rather than monthly basis. In the first year of work attempts, any amount of earnings could be made with no impact on cash benefits. However, if at least $13,920 were earned during that year, then in the second year, a $1-for-$2 offset would apply to benefits above the trial work level. Benefit eligibility would terminate thereafter (along with Medicare coverage) if $52,320 were earned in that second year (assuming the average benefit amount) or any year thereafter; otherwise, eligibility for benefits would continue.

All other incentive rules—such as SGA, unsuccessful work attempt, extended period of eligibility, expedited reinstatement and initial reinstatement periods, and special self-employment effort tests—would be eliminated. This approach would remove the unfairness of, and disincentive created by, the cash cliff. These changes would greatly simplify the program, ease the administrative burden on SSA, and enhance beneficiary understanding. Moreover, this proposal strikes the right balance between encouraging substantial work, not penalizing work attempts, minimizing beneficiary risk, and avoiding potential gamesmanship in the timing of work.

Based partly on the demonstration project results, it is likely that this proposal would lead to a few more benefit terminations than currently, but would also increase the cash benefits provided to those who work. While this would modestly raise the net costs of the Disability Insurance program, the combined income and payroll taxes paid on increased earnings, stricter cutoff of Medicare, and getting health coverage instead from employers or the exchanges would likely bring the overall cost to the federal government and taxpayers closer to budget-neutral. Given the radical rule simplification, SSA’s work incentive counseling support could be discontinued, along with the failed Ticket to Work program, reverting to state vocational rehabilitation programs. This reform proposal, which would require legislation, should be paired with the long-overdue regulatory effort to simplify and modernize the vocational data and rules used to determine eligibility for disability benefits.

The disability benefits offered by the federal government are a lifeline to millions of Americans. It is our responsibility, though, to ensure the system is approachable to those who need it, and fair to the taxpayers footing the bill. This proposal strikes that balance.

Mark J. Warshawsky is a senior fellow and Wilson H. Taylor Chair in Health Care and Retirement Policy at the American Enterprise Institute, where he focuses on Social Security and retirement issues, pensions, long-term care, disability insurance, and the federal budget.